Chicago’s Natural Divisions and Plant Communities

by Swink and Wilhelm

These texts are transcribed from Plants of the Chicago Region, by Floyd Swink and Geroud Wilhelm.1 Wilhelm has since published a more up-to-date text for botanists, but the following chapters are out of print: the collection of primary texts from presettlement is especially notable. The citations have been checked and linked when available. ~

Natural Divisions of the Chicago Region

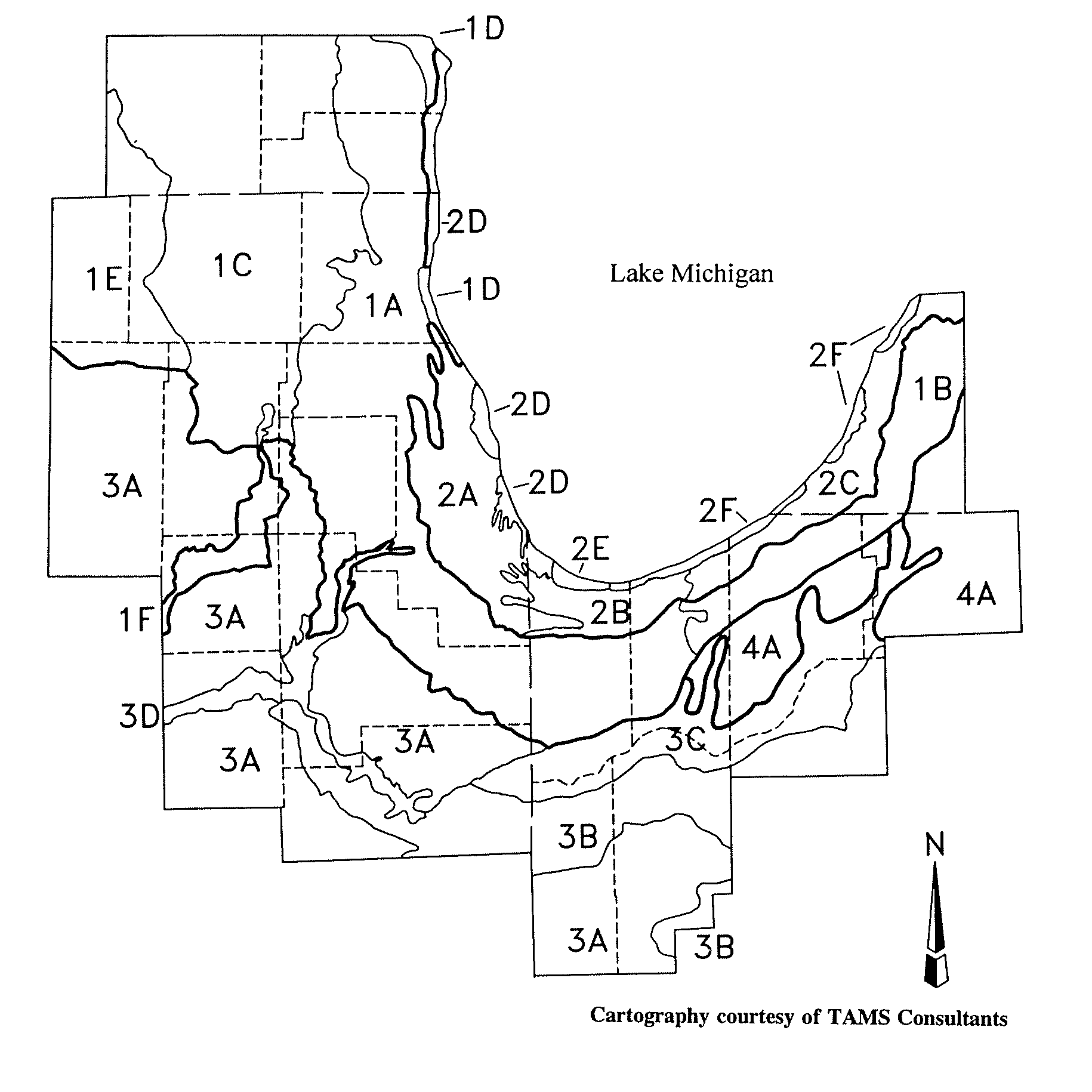

The authors are indebted to Kenneth Mierzwa of TAMS Consultants, Inc., Chicago, Ill., for having made available for this book a synopsis of the Natural Divisions of the Chicago Region, a distillation of a forthcoming paper.

Homoya et al.2 describe a natural division as a “generalized unit of the landscape where a distinctive assemblage of natural features is present.” Natural divisions maps are a synthesis of geology, physiography, soils, hydrology, presettlement vegetation, and characteristic fauna. They soon will be available for all four of the states included within the Chicago region.23456 The current effort combines maps of the four states and adds additional detail that reflects the regional scale. For example, the Morainal Section in Illinois3 and the Valparaiso Moraine Section in Indiana2 are valid concepts when viewed within the context of each state, but when this section is extended along the Valparaiso and associated moraines from Wisconsin to Michigan, it must be split at some point. The beech-maple forests of our eastern section are too distinct from the oak savannas and prairies of our western section to be included in the same unit. Similarly, the lake plain is elevated to division status, and subdivided to reflect significant differences among the black-soil prairies once present on the site of modern-day Chicago, the sand savannas of much of the northwestern Indiana lake plain, and the more heavily wooded lake plain of Michigan and adjacent Indiana. These new boundaries address the east to west transition from forest to prairie.

Morainal Natural Division

Young and rolling morainal topography close to Lake Michigan. The boundary follows the outer edge of the Valparaiso Moraine except in the northwest, where the line is based on geological features and presettlement vegetation.3

1A. Western Morainal Section

Mostly end moraines. Soils with a high clay content and often a perched water table. Primarily prairie and savanna, with isolated areas of mesic woodland and forest.

1B. Eastern Morainal Section

Eastern portion of the Valparaiso Morainal system. Geologically similar to 1A, but a break is made based on the predominant plant communities. Mostly timbered with savannas and forests.

1C. Kettle Moraine Section

Characterized by truncated end moraines, outwash features, kame and kettle topography, an unconsolidated aquifer, and glacial lakes. Savannas were once the principal plant community, interspersed with prairies, sedge meadows, fens, small spring-fed streams, and marshes.

1D. Racine Till Plain Section

Mostly end and ground moraines; timbered principally with mesic savanna or forest. Ravines along Lake Michigan include a number of boreal relict plants.

1E. Winnebago Drift Section

Altonian substage of the Wisconsinan glaciation, earlier than other sections of the Morainal Natural Division. Topography somewhat more level and wetlands less common; streams more entrenched and drainage patterns better developed. Savannas and dry prairies predominated.

1F. Fox River Bluff Section

Characterized by moderately high bluffs along the lower Fox River Valley, and associated outwash features and dolomite outcrops. Seepage areas and fens occur along the bluffs. Included within the Morainal Division because of the fens similar to those in 1C, and extensive woodlands associated with the bluffs.

Lake Plain Natural Division

Characterized by lacustrine deposits and aeolian dunes. Included within the Morainal Division by previous authors.

2A. Chicago Lake Plain Section

Once covered by glacial Lake Chicago; consists of nearly level lacustrine silt and clay deposits. Mesic and wet prairie and marsh originally extensive.

2B. Gary Lake Plain Section

Includes the Tolleston, Calumet, and Glenwood beach ridges and intervening often slightly acidic sand flats. Characterized by sand savannas with intervening wet sand prairies and marshes.

2C. Benton Harbor Lake Plain Section

Topographically similar to 2B, but originally mostly wooded with rich swamps and mesic forests.

2D. Illinois Dunes Section

Low beach ridges and swales at Illinois Beach State Park and Chiwaukee Prairie support an open community of sand prairie, sand savanna, and marsh. Two additional sand areas of irregular shape which once existed on the lake plain were probably similar; these are within the present limits of Evanston and Chicago.

2E. Ridge and Swale Section

Formed only within the past 6000 years, characterized by alternating parallel low ridges and swales. Ridges consist of relatively alkaline sandy soils and are covered by sand prairie and a sparse savanna of black oak and jack pines, wetlands characterized by pannes and open water.

2F. High Dune Section

Narrow band along Lake Michigan; includes a unique high dune complex of communities. Prevailing winds which build the dunes also bring higher than normal snowfall, moderate temperatures, and new sand. Regularly timbered with black oak and white pine savanna, becoming more regularly forested northward.

Grand Prairie Natural Division

The grand prairie once covered much of east-central Illinois. The northeastern portion of this natural region enters the Chicago region.

3A. Grand Prairie Section

Mostly end and ground moraines; level to gently rolling. Characterized by tallgrass prairie, with timbered communities limited to the margins of rivers and well-drained morainic ridges.

3B. Kankakee Sand Section

Aeolian and lacustrine sand deposits, mostly on the south side of the Kankakee River. Sand savannas are frequent on dunes, interspersed with wet to dry sand prairie, sand flatwoods, marsh, and shrub swamps.

3C. Kankakee Marsh Section

Vast wetlands which once bordered the Kankakee River in Indiana; marsh was probably the predominant community type, areas of true swamp and riparian savanna were present.

3D. Bedrock Valley Section

Dolomite exposed along the Des Plaines River by scouring from the outflow of glacial Lake Chicago. The Kankakee torrent cut down to underlying dolomite from Momence to the confluence with the Des Plaines. In the Illinois River Valley, shale and sandstone exposures are more prevalent. Unique communities include dolomite cliffs and prairie, typically interspersed with sedge meadow and marsh.

Glacial Lakes Natural Division

Only one section of the Northern Lakes Division enters the eastern part of our region.

4A. Glacial Lakes Section

Exhibits complex and uneven ice-contact terrain deposited by a stagnating glacier.4 Moraines, kames, and outwash plains are present, and kettle ponds, lakes, and swamps are numerous. Extensive forests, with savannas on steep slopes. Lakes, swamps, bogs, fens, and marshes are interspersed. This section is expanded to include a gravel outwash fan, formerly mapped as part of 3B.

Natural Plant Communities

The Chicago region, situated at the southern end of Lake Michigan, lies along the northeastern edge of the Tall Grass Prairie biome of the Midwest. The prevailing landscape at the time of settlement was open prairie. In some areas the prairie was flat, in others rolling.

Undoubtedly, the most remarkable feature of the state of Illinois is its extensive prairies, or non-wooded tracts. They begin on a comparatively small scale in the basin of lake Erie, and already form the bluff of the land about lake Michigan, the Upper Wabash, and the Illinois, … or rather, the whole of this tract may be described as prairie intersected by patches of woodland, chiefly confined to the river valleys. The characteristic peculiarity of the prairies is the absence of timber; in other respects, they present all the varieties of soil and surface that are found elsewhere; some are of inexhaustible fertility, others of hopeless sterility; some spread out in vast boundless plains, others are undulating or rolling, while others are broken by hills. In general, they are covered with a rich growth of grass, forming excellent natural meadows, from which circumstance they take their name. Prairie is a French word, signifying meadow, and is applied to any description of surface that is destitute of timber and brushwood, and clothed with grass. Wet, dry, level, and undulating, are terms of description merely, and apply to prairies in the same sense as they do to forest lands. The prairies of Illinois may be classed under three general divisions;–the healthy, or bushy; the alluvial, or wet; and the dry, or undulating. Those [that] have springs of water, … are covered with bushes of hazel and furze, small sassafras shrubs interspersed with grape-vine, and in the season of flowers become beautifully decorated by a rich profusion of gay herbaceous plants.7

The prairies were regularly interspersed with poorly drained flatland, and the hills were commonly characterized by hanging fens and seepage slopes where the water-filled high grounds discharged a constant flow of clear water into wet meadows and marshes.

Between the Plein and Theakaki, the country is flat, wet, and swampy, interspersed with prairies of an inferior quality of soil.8

Throughout the region were small to large tracts of savannas consisting of open-grown timbers, mostly of Bur and White Oak. Eastward, around the southern tip of Lake Michigan, the lake shore rose up in high wooded dunes covered mostly in White Pine.

The northern part of Illinois is beautifully diversified with groves of timber and rolling prairies. The shores of Michigan have a large supply of pine timber, and from this source the lumber for buildings at Chicago is obtained. … The stage road, from Michigan City to Chicago, is, most of the way, on the sandy beach. Chicago … is built on a level prairie, open in full view to the Lake, and the soil is enough mixed with sand, to prevent its being muddy.9

… there were along where Michigan Avenue now is walled with palatial mansions innumerable sand hills rising to a considerable height, overrun by the wild juniper loaded with its fragrant berries at the feet of which stretched away to the southeast the soft smooth beach of firm glistening sand … along the beach north of the river where also the drifting sand has been piled by the shifting winds into a thousand hills stretching farther back from the waters than on the south, but here the juniper bush was replaced by a stunted growth of scraggy pines often hilled up by the drifting sand. … Further back was a broad ramble among stately oaks sparsely scattered over the even plain among which a horseman could be seen at a great distance.10

Behind the dunes were vast wet prairies and marshes, which, eastward and northward, gave way to huge swamps of mixed hardwood forests. East of the windward shores, in the lee of the dunes and beyond, the timbers closed up in spots into tighter savannas and cool forests of Sugar Maple and Beech; but the timbers soon opened up again into scattered groves and prairies.

On the one hand stretched bur-oak plains, spread with a verdant carpet, variegated with dazzling wild flowers, without an obstacle to intercept the view for miles, save the sombre trunks of the low oaks, sparsely spreading their shadows across the lawn; on the other hand arose the undulations of the white oak openings, with picturesque outlines of swales and slopes gracefully sweeping and sharply defined in the distance. Then, there lay the majestic prairie, grand in expansive solitude, its fringe of timber, as seen in the distance, resembling a diligently trained and well-trimmed garden parterre.11

Southward and westward, the landscape was broken by large streams, with flat prairie bottoms and scattered stretches of tree-lined bluffs and backwaters.

The roads in this country are in a state of nature, But the ground is so smooth, and so entirely free from stones, that when the earth is dry you do not find better roads at the north. … We took the Galena road, forded the river, a stream about four rods wide, and passed on, over a beautiful, open prairie country, here and there a log house, a small grove of timber, or small stream of water; the land high, dry and rich, and arrived at night at Naper’s settlement, on the Du Page River, thirty-seven miles from Chicago. … We now left the Galena road and took a course more northerly to the Big and Little Woods, on [the] Fox River. In travelling twelve miles we came to the settlement, at the lower end of “Little Woods.” … houses were built near the timber, and a beautiful rich prairie opened before them. … [The] Fox River is a clear stream of water, about twenty rods wide, having a hard limestone bottom, from two to three feet deep, a brisk current, and generally fordable. On its banks, and on some other streams, we occasionally found ledges of limestone; but other than that, we found no rocks in the State. We here forded the river, and travelled all day on its western bank. We found less timber on this side of the river. On the east side, it is generally lined with timber to the depth of a mile or more; but the west side is scarcely skirted with it. It is somewhat singular and unaccountable, but we found it universally to be the fact, that the east side of all the streams had much the largest portion of timber.9

All of the streams in the northern parts of the state, which empty into the Wabash and Illinois, have their branches interwoven with many of the rivers running into lake Erie and Michigan. … [T]hey not unfrequently issue from the same marsh, prairie, pond, or lake. The … portage between the Chicago and the Kickapoo [Des Plaines] branch of the Illinois, [is] rendered important by the inundations, which at certain seasons cover the intermediate prairie, from which the two opposite streams flow. By this means nature herself opened a navigable communication between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi; and it is a fact, however difficult it may be of belief to many, that boats not unfrequently pass from Lake Michigan into the Illinois, and in some instances without being subjected to the necessity of having their lading taken out.8

The country back of Chicago, for the distance of twelve miles, is a smooth, level prairie; producing an abundance of grass, but too low and wet for cultivation. The Chicago River is formed by two branches, which meet at the upper end of the village. The branches come from exactly opposite directions and after running some distance, parallel with the lake, and about a mile from it, here meet each other, and turning at right angles, flow in a regular straight channel, like a canal, into the lake. On each side of the town, between these branches and the lake shore, there is, for some distance, a good growth of wood and timber. On the lake shore, there are naked sand hills; and these are found all around the lake. … If Lake Michigan were ten feet higher than its present level, its waters would flow into the Illinois river. The Oplanes, a branch of the Illinois, approaches within twelve miles of the Lake; and the land between is low and level. When the water is high, boats now pass from the lake to the river. At a time of high water, a steamboat attempted to pass from the Illinois to the lake. After running a day from Ottawa up the river, the water began to subside, the captain became alarmed, lest his boat might run aground and returned.9

The alluvial, or wet prairies, are generally on the margins of the great water courses, though sometimes they are at a distance from them; their soil is deep, black, friable, and of exhaustless fertility. … From May to October, the prairies are covered with tall grass and flower-producing weeds. In June and July, they seem like an ocean of flowers of various hues, waving to the breezes which sweep over them. The numerous tall flowering shrubs and vegetables which grow luxuriantly over these plains, present a striking and delightful appearance.7

The landscape was replete with wet depressions, and, particularly northwestward in our region, surrounded by copses of larch, and then by shrubs and sedge meadows. Such landscapes were burned on a regular basis.

The dry or undulating prairies are almost destitute of springs and of all vegetation, with the exception of weeds, flowers, and grass. The undulations are so slight that, to the eye, the surface has almost the appearance of an uninterrupted level, though the ravines made by freshets show that there is a considerable degree of inclination. In the prairie region there are numerous ponds, formed some from the surface water, the effect of rain, and the melting of the snows in the spring and others near the rivers from their overflowing.7

The prairies are all burnt over once a year, either in spring or fall, but generally in the fall; and the fire is undoubtedly, the true cause of the origin and continuance of them. In passing through the State I saw many of them on fire; and in the night, it was the grandest exhibition I ever saw. A mountain of flame, 30 feet high, and of unknown length, moving onward, roaring like ‘many waters’–in a gently, stately movement, and unbroken front–then impelled by a gust of wind, suddenly breaks itself to pieces, here and there shooting ahead, whirling itself high in air–all becomes noise, and strife, and uproar, and disorder. Well might Black Hawk look with indifference on the puny exhibition of fireworks in New York, when he had so often seen fireworks displayed, on such a gigantic scale, on his own native prairies.9

For most writers today, our landscape no longer evokes such eloquence. To the extent that the natural landscape is described at all, it is done so very clinically, mostly yielding codifications of plant communities. Such taxonomies are facilitated by the fact that our natural communities are fragmented into disparate pieces, with many of the intervening, and possibly confounding, communities gone forever.

Attempting to discriminate plant communities from among the myriad of plant associations is, nonetheless, a pursuit of botanists seeking to assign each plant a “proper” and definable place in the landscape. Part of the challenge is to give each community a name which consists of two or three words from the English dictionary. Commonly used words include nouns such as forest, swamp, savanna, flatwoods, prairie, meadow, fen, and bog, and adjectives such as acidic, alkaline, wet, mesic, dry, sandy, mucky, and loamy. The difficulty begins when the default assumption is made that if the words do not exist, the community cannot exist. In the taxon entries we have avoided forcing the native species into formally circumscribed plant communities, choosing instead to use common English prose and a list of immediate associates to describe the habitat. While our native plants are prevailingly faithful to some natural context, a disciplined attempt to place even a small percentage of the 1,638 elements into one or more formally designated categories, however permutated, quickly informs the botanist of the folly of this exercise.

Another factor complicating plant community classification is the fact that soon after the Native American culture was replaced by the European culture changes in the human relationship with the landscape caused fundamental changes in plant community composition. Cessation of fire, straightening of rivers, ditching, tiling, heavy grazing, and urban and suburban infrastructure have so modified the original structure and depauperized the land that our ability to piece together an understanding of natural order is profoundly compromised. About 90 percent of our native flora is restricted to the stable habitats provided by our original plant communities,12 so an understanding and stewardship of such areas is critical if we are to carry forward into the future a possibility of association with living things other than ourselves, a few weeds, and cultivars.

Given all the problems associated with trying to envision and describe the natural plant communities, we nevertheless will propose a paradigm of plant communities. While these communities are certainly more artifacts of binary thinking than representative of nature, a brief synopsis can communicate to a botanist information on the nature of our flora and landscape. An intellectual miscarriage occurs only when it is pretended that such community constructs are or could be “scientifically” abstracted.

Generally, one can visualize about nine principal kinds of communities: aquatic, marsh, fen, bog, swamp, forest, savanna, dune, and prairie. With the exception of certain dune, bedrock, or coastal-plain disjunct systems, most of these general community groups are variously expressed in the different natural divisions and sections (see page 38). In choosing representative species, we have generally chosen a few very conservative species to which the user can refer in the annotated checklist for further associates and nuances of habit, distribution, and more detailed interpretations of the plant community. These representative species are not intended to represent associations for specific kinds of plant communities; rather, each species tends to represent a facet or variant of the general community type. The word “characteristic,” when used in connection with species listed under the community descriptions, does not necessarily mean that the species are common or even locally extant in the community; rather, it is meant to imply that the species are typical of or restricted to the community, and that habitat discussions under those species in the annotated checklist amplify the character of the community. Another type of natural community in the Chicago region is the ruderal flora, principally those species with C values 0 or 1.1

Aquatic

Aquatic plant communities were occasional throughout the region but most abundant in our eastern and northwestern sectors. They formed in the landscape in potholes and in lacustrine plains where there was no discharge. Since our region evaporates nearly or quite as much water as falls, aquatic communities are sustained by waters from a surrounding watershed in excess of that provided by rain over their surfaces. Generally, these excess waters filter down through vegetated ground into the underlying soil until they reach impervious material, and exit by way of springs, rills, or ground water. Along our major streams, aquatic plant communities developed in alluvial sloughs and ponds derived from surface melt or runoff waters.

The more minerotrophic or ground-water communities are characterized by plants such as Brasenia schreberi, Hippuris vulgaris, Megalodonta beckii, Myriophyllum verticillatum pectinatum, Potamogeton amplifolius, Potamogeton richardsonii, Potamogeton strictifolius, Utricularia vulgaris, and Zannichellia palustris. In softer waters one is more likely to encounter plants such as Nuphar advena, Nuphar variegatum, Nymphaea tuberosa, Utricularia geminiscapa, and Utricularia purpurea. Alluvial or surface water communities are characterized by members of the Lemnaceae, Ceratophyllum demersum, Potamogeton foliosus, Potamogeton pectinatus, Potamogeton illinoensis, and Potamogeton natans.

Marsh

Marsh plant communities generally occur along the transition between aquatic communities and drier communities, or in large flats which are regularly inundated by shallow surface waters for much of the growing season. Marshes are best developed with us in the Lake Plain, in the lacustrine flats of our northwestern and eastern sectors, and along the lower reaches of the Des Plaines and Kankakee river drainages. These communities are best characterized by emergent species such as Carex aquatilis, Carex lacustris, Hydrocotyle umbellata, Hypericum boreale, Peltandra virginica, Pontederia cordata, Sagittaria graminea, Sagittaria latifolia, Sagittaria rigida, Scirpus subterminalis, Scirpus validus creber, Sparganium americanum, Sparganium chlorocarpum, Sparganium eurycarpum, and Zizania aquatica. On the shores of ponds, lakes, and swales, often growing without heavy competition, conservative species include Cyperus diandrus, Eleocharis geniculata, Juncus pelocarpus, Peplis diandra, Rotala ramosior, Scirpus purshianus, Scirpus torreyi, Sparganium chlorocarpum, Utricularia gibba, Veronica comosa, and Veronica scutellata. A related community, with affinities to fens and wet prairies, is the sedge meadow. It develops in large, shallow, lacustrine flats, and is dominated by hummocks of sedges, particularly Carex stricta, and characterized by conservative species such as Aster puniceus, Carex buxbaumii, Carex atriculata, Dulichium arundinaceum, Lysimachia terrestris, Lysimachia thyrsiflora, Rumex orbiculatus, Sium suave, and Utricularia vulgaris.

Fen

Fens are wetland communities which occur in areas where the glacial formations are such that carbonate-rich ground water discharges at a constant rate along the slopes of kames, eskers, moraines, river bluffs, or even dunes, or in flats associated with these formations, provided the material through which the waters traveled is rich in calcium or magnesium carbonates. Depending upon the circumstances fens can occur where marl is at or near the surface or where peats are constantly bathed in minerotrophic ground water; such areas can be wooded or open.

Marly fens are commonly on open prairie slopes and are characterized by Carex sterilis, Eleocharis rostellata, Rhynchospora capillacea, Scirpus cespitosus callosus, Tofieldia glutinosa, and Triglochin palustris. In the constantly flowing rills discharging in these fens grow Agrostis alba palustris, Armoracia aquatica, Berula erecta, and Mimulus glabratus fremontii. Related to the hillside fens are the wooded seeps which occur sporadically on steep bluffs. Characteristic species include Aster prenanthoides, Cimicifuga racemosa, Fraxinus nigra, Polymnia canadensis, Rhamnus alnifolia, Rhamnus lanceolata, Thuja occidentalis, Ulmus thomasii, and Veronica americana. As fens become peatier characteristic species include Betula pumila, Campanula uliginosa, Conioselinum chinense, Eriophorum angustifolium, Filipendula rubra, Galium asprellum, Habenaria lacera, Phlox maculata, Pogonia ophioglossoides, Patentilla fruticosa, Salix candida, Saxifraga pensylvanica, Solidago uliginosa, and Valeriana uliginosa. The flat, black-soil prairie fens are characterized by Aster borealis, Carex interior, Carex prairea, Cirsium muticum, Cypripedium candidum, Habenaria hyperborea huronensis, Lobelia kalmii, Muhlenbergia glamerata, Parnassia glauca, Satureja arkansana, Scleria verticillata, Selaginella apoda, and Valeriana ciliata.

Bog

Bog, like most of the other terms used here to describe plant communities, is not a scientific word in the sense that its use always signifies a uniform, unique concept which is standardly perceived. Any place, for example, where there is a quagmire or wet, mucky, hummocky ground is likely to be termed a “bog;” hence, the expression “bogged down.” The contemporary ecologist tends to restrict the term “bog” to a hydric/edaphic vegetational scenario which is typified by acidic, usually organic substrates, and a characteristic floristic composition. Many of our peatlands are influenced significantly by waters rich in carbonates and can be called prairie fens. But as the cation exchange capacity damps off bog-like conditions can begin to develop. Many of the bogs in our northwestern sector can be called alkaline bogs for that reason.

Commonly the peatland floats on a minerotrophic head of water, with the deeper roots thus exposed to calcareous or circumneutral conditions, and the shallower roots are imbedded in the upper sphagnum mat, probably in a more acidic environment. Characteristic species in these minerotrophic or alkaline bogs include Carex brunnescens, Carex diandra, Carex lasiocarpa americana, Carex leptalea, Geum rivale, Hypericum virginicum fraseri, Larix laricina, Menyanthes trifoliata minor, Potentilla palustris, Rhus vernix, Rhynchospora alba, Ribes hirtellum, Salix pedicellaris hypoglauca, Salix serissima, Sarracenia purpurea, Utricularia intermedia, and Utricularia minor. In large basins or in areas where the influence of minerotrophic waters is insignificant, characteristically acid bogs can develop, inhabited by plants such as Andromeda glaucophylla, Arethusa bulbosa, Carex atlantica capillacea, Carex canescens, Carex chordorrhiza, Carex disperma, Carex echinata, Carex limosa, Carex oligosperma, Carex pauciflora, Carex tenuiflora, Carex trisperma, Chamaedaphne calyculata angustifolia, Cypripedium acaule, Drosera intermedia, Drosera rotundifolia, Eriophorum gracile, Eriophorum spissum, Eriophorum virginicum, Habenaria blephariglottis, Habenaria ciliaris, Hypericum virginicum, Salix sericea, Scheuchzeria palustris americana, Utricularia geminiscapa, Vaccinium macrocarpon, Vaccinium oxycoccos, Viola pallens, and Woodwardia virginica. Related to the acid bog, often in sand flats or basins, are floating sedge mats that rise and fall with the water table. Such mats are characterized by Eleocharis robbinsii, Eriocaulon septangulare, Fuirena pumila, Hypericum canadense, Rhexia virginica, and Scirpus smithii.

Swamp

Swamps are wetlands characterized by trees growing in large flats or basins that are poorly drained, with most of the water leaving through evapotranspiration. They can occur in the backwaters of large, slow moving rivers, such as the Kankakee, or in wet sandy flats in the Kankakee Sand Section south of the Valparaiso Moraine. They also occur on the moraine in wet depressions. North of the Valparaiso Moraine, in the Lake Plain, they are best developed in the large flats behind the high dunes.

Along the Kankakee River they occur in bottomlands, with characteristic species including Carex typhina, Cephalanthus occidentalis, Fraxinus pennsylvanica subintegerrima, Fraxinus tomentosa, Mikania scandens, Populus heterophylla, and Styrax americana. In sandy, poorly drained flats with a high water table, a fire-dependent savanna-like swamp dominated by Quercus palustris is characterized by Bartonia virginica, Betula nigra, Carex haydenii, Carex longii, Carex straminea, Eleocharis tenuis verrucosa, and Rubus hispidus. On the moraines, especially the Valparaiso and Lake Border moraines, there are shallow depressions characterized by Quercus bicolor; other characteristic species include Carex crus-corvi, Carex lupuliformis, Carex muskingumensis, Carex squarrosa, Carex tuckermanii, Carex vesicaria monile, Cephalanthus occidentalis, Fraxinus nigra, Onoclea sensibilis, and Lycopus rubellus. There is a phase of this swamp on the low terraces of the Kankakee River, characterized by Carex grayii, Carex lupulina, Carex muskingumensis, Leersia lenticularis, Lysimachia hybrida, and Quercus bicolor.

In the broad low flats behind the high dunesof Lake Michigan lies one of the richest and most complicated forested systems in our region. It is characterized by a complex hydrology and is interspersed by gentle rises, shallow depressions, and hummocks, and consists of an inseparable mixture of wooded fen, bog, and mesic forest. It supports a wide array of species, including trees such as Acer saccharum, Betula alleghaniensis, Betula papyrifera, Fagus grandifolia, Quercus bicolor, Quercus palustris, Quercus rubra, and Tilia americana; other characteristic species include Carex bromoides, Carex crinita, Carex debilis rudgei, Carex folliculata, Carex intumescens, Carex seorsa, Chrysosplenium americanum, Coptis trifolia, Cypripedium calceolus pubescens, Dryopteris cristata, Habenaria clavellata, Habenaria flava herbiola, Habenaria psycodes, Lycopodium lucidulum, Lycopodium obscurum, Medeola virginiana, Milium effusum, Nemopanthus mucronata, Poa paludigena, Rubus pubescens, Trientalis borealis, and Viola incognita. Such swamps, while they retain their essential characteristics, change in specific species composition as one travels northeastward from Dune Acres in Porter County to Benton Harbor in Berrien County.

Forest

Forests occur in our eastern sector on rises which are relatively well drained and physiographically located such that exposure to fire is rare. Such forests are dominated by Acer saccharum and Fagus grandifolia. The ground cover vegetation is not physiognomically capable of sustaining a line of fire. Characteristic species include Athyrium pycnocarpon, Athyrium thelypterioides, Carex amphibola, Carex careyana, Carex deweyana, Carex digitalis, Carex laxiflora, Carex leptonervia, Carex plantaginea, Carex prasina, Corallorhiza maculata, Cornus rugosa, Dentaria diphylla, Dicentra canadensis, Dirca palustris, Dryopteris hexagonoptera, Dryopteris marginalis, Dryopteris noveboracensis, Galium circaezans, Galium lanceolatum, Hieracium paniculatum, Hydrophyllum canadense, Lonicera canadensis, Maianthemum canadense, Mitella diphylla, Panax trifolius, Panicum commutatum ashei, Panicum dichotomum, Poa alsodes, Pyrola asarifolia purpurea, Sambucus pubens, Tipularia discolor, and Viola rostrata. Another type of forest is along the high dunes, northward in Berrien County, characterized by Betula alleghaniensis, Cornus rugosa, Dirca palustris, Fagus grandifolia, Taxus canadensis, and Tsuga canadensis.

A relative of our eastern forest occurs on the western bluff of Lake Michigan in the deep morainic dissections or ravines. Here also grow Acer saccharum and Fagus grandifolia, but the ground cover vegetation is such that sporadic ground fires could creep down the slopes from the savannas on the higher, more level ground, and nose slopes. Characteristic species include Betula papyrifera, Carex pedunculata, Dryopteris filix-mas, Matteuccia struthiopteris, Poa languida, Populus balsamifera, Prunus nigra, Pyrola elliptica, and Shepherdia canadensis. Pinus resinosa may also have grown here.

Savanna

Savannas, as interpreted here, include those portions of our wooded landscape in which structure was, to one degree or another, affected by fires set by Native Americans in the thousands of years before European settlement. Generally, these communities were intercalated among the prairies and developed a ground-cover vegetation which would carry at least occasional fires in the autumn, when their surrounding prairies were wont to burn. Such savannas ranged in character from completely closed and forest-like, to very open with only scattered trees.

Most related to the forest communities are mesic savannas. These are closed-canopy woodlands, dominated by Acer nigrum and Quercus rubra, and with a graminoid ground cover capable of sustaining small but occasional ground fires. Such savannas are best developed on north- and east-facing slopes in dissected or topographically complex portions of the moraines. Characteristic species include Actaea rubra, Adiantum pedatum, Agrimonia rostellata, Arabis canadensis, Aralia racemosa, Aristolochia serpentaria, Aster furcatus, Aureolaria virginica, Brachyelytrum erectum, Carex gracillima, Carex hitchcockiana, Carex laxiculmis, Carex shortiana, Carex woodii, Cercis canadensis, Collinsia verna, Conopholis americana, Diarrhena americana, Dryopteris goldiana, Habenaria viridis bracteata, Jeffersonia diphylla, Linum virginianum, Lonicera dioica, Morus rubra, Muhlenbergia sylvatica, Orchis spectabilis, Poa sylvestris, Sanicula trifoliata, Scutellaria ovata versicolor, and Trillium grandifiorum.

On the more undulating, well drained, but fertile morainic ridges and knolls are the dry-mesic savannas dominated by Quercus alba and Quercus macrocarpa. It is probable that portions of such woodlands burned fairly regularly, and carried low but steady lines of flame. Characteristic species include Agalinis gattingeri, Arenaria lateriflora, Aster schreberi, Bromus purgans, Camassia scilloides, Carex hirtifolia, Carex oligocarpa, Carex pensylvanica, Carya ovata, Corylus americana, Dodecatheon meadia, Erigeron pulchellus, Eupatorium sessilifolium brittonianum, Helianthemum bicknellii, Heuchera richardsonii, Hystrix patula, Krigia biflora, Lathyrus ochroleucus, Lechea intermedia, Monotropa uniflora, Orobanche uniflora, Silene virginica, Swertia caroliniensis, Taenidia integerrima, Trillium sessile, and Vici caroliniana.

On the nearly level or gently undulating moraines are the open savannas of heavier soil characterized by open-grown trees of Quercus macrocarpa. Such savannas have a well developed graminoid ground cover, and carry substantial fires on a regular basis. These savannas developed on low mounds within the mesic or wet prairies, or in transitional zones between the lower prairies and the dry prairies of kames and eskers. Little is known about the conservative flora of these savannas, but species which we associate with the Bur Oak include Andropogon gerardii, Carex pensylvanica, Carya ovata, Corylus americana, Galium concinnum, Helianthus hirsutus, Hypoxis hirsuta, Lilium michiganense, Rosa setigera, Solidago juncea, Thalictrum dasycarpum, Trillium recurvatum, and Veronicastrum virginicum.

In sandy soils, especially in our eastern sector, along well drained ridges and old dunes, the savannas are dominated by Quercus velutina. Such savannas are closely associated with sand prairies, and the two communities have many species in common. The sand savannas burn regularly and are characterized by species such as Aralia hispida, Aster linariifolius, Baptisia tinctoria crebra, Campanula rotundifolia, Carex siccata, Chimaphila umbellata cisatlantica, Corydalis sempervirens, Galium pilosum, Liatris aspera, Lysimachia quadrifolia, Monotropa hypopithys, Pteridium aquilinum latiusculum, Rubus enslenii, Spiranthes lacera, and Vaccinium angustifolium.

It would seem that there is a close association between the sand savannas and what once were pine savannas near the southern shore of Lake Michigan, where Pinus strobus was plentiful along the dunes. There remain a few isolated stands where one can only imagine what species once characterized these pine savannas. It was probably in these pine savannas wherein resided such now rare plants as Arctostaphylos uva-ursi coactilis, Epigaea repens, Habenaria hookeri, Lactuca hirsuta, Melampyrum lineare latifolium, Oryzopsis pungens, and Polygala paucifolia. Probably also included here are the associates of Carex eburnea, Celtis tenuifolia, Chimaphila maculata, Juniperus communis, Oryzopsis asperifolia, and Pyrola rotundifolia americana. Farther north, along the high dunes, the pine savannas give way to a wooded dune forest.

Dune

On the open sand of foredunes of Lake Michigan is a special habitat characterized by species which grow locally only in the dunes near the lake. These include Ammophila breviligulata, Cakile edentula, Cirsium pitcheri, Euphorbia polygonifolia, Lathyrus japonicus glaber, Salix syrticola, and Solidago racemosa gillmanii. Confined to the lower dunes along the western shore of Lake Michigan is Juniperus horizontalis. In the more active sands in the dunes of our eastern sector grow Hudsonia tomentosa, Polygonella articulata, and Selaginella rupestris.

In wet, interdunal flats (pannes), where sand has been blown out down to the water table, is a plant community generally characterized by species such as Carex aurea, Carex garberi, Gentiana crinita, Hypericum kalmianum, Sabatia angularis, Triglochin maritima, and Utricularia cornuta. The pannes near Ogden Dunes, Porter County, are characteristically surrounded by small forests of Pinus banksiana. Related to both the pannes and the prairie fens is a kind of wet alkaline prairie, characterized by plants such as Agalinis skinneriana, Carex conoidea, Carex crawei, Carex flava, Carex viridula, Castilleja coccinea, Cladium mariscoides, Cypripedium calceolus parviflorum, Eleocharis compressa, Panicum boreale, and Scleria triglomerata.

Prairie

The prairies comprise those plant communities that are dominated by a diversity of perennial forbs growing in a perennial graminoid matrix, which forms a dry flammable turf in autumn. A part of the habitat of our prairies was the regular autumnal fire, which, lacking a regular occurrence of dry lightning, was set annually by the Native Americans. Prairies developed on those substrates in which the aboveground perennial phytomass produced more fixed carbon annually than was likely to be grazed or decomposed. In our area prairie communities range from wet to dry and once dominated much of the landscape, intercalating or even blending with savannas and fens.

To a Midwesterner, perhaps the first image evoked with the term prairie is that of the tall grasses of Andropogon gerardii and Sorghastrum nutans in their full, late-summer development–“high as a man on a horse,” interspersed with the rosinweeds, sunflowers, and asters. Such are the mesic prairies; conservative species within them include Baptisia leucophaea, Cacalia plantaginea, Carex bicknellii, Eryngium yuccifolium, Gentiana andrewsii, Gentiana puberulenta, Habenaria leucophaea, Lilium philadelphicum andinum, Panicum leibergii, Sisyrinchium albidum, and Sporobolus heterolepis. A wetter variant of the mesic prairie is more likely to be dominated by Calamagrostis canadensis and Spartina pectinata, with Aster puniceus firmus, Beckmannia syzigachne, Chelone glabra, Eleocharis wolfii, Lysimachia quadriflora, Oenothera perennis, Oenothera pilosella, Pedicularis lanceolata, and Solidago ohioensis, and in its best development is fen-like.

In the drier prairies Andropogon scoparius and Stipa spartea are commonly the more obvious grasses, with conservative species including Agalinis aspera, Asclepias viridiflora, Aster ptarmicoides, Aster sericeus, Astragalus tennesseensis, Blephilia ciliata, Bromus kalmii, Carex meadii, Cirsium hillii, Convolvulus spithamaeus, Helianthus occidentalis, Panicum perlongum, Polytaenia nuttallii, Psoralea tenuifoa and Zizia aptera. Another kind of dry prairie occurs in the Kettle Moraine Section, or our northwestern sector and, growing among short warm-season grasses like Bouteloua curtipendula, characteristic species include Agoseris cuspidata, Allium stellatum, Anemone patens wolfgangiana, Artemisia serrata, Asclepias lanuginosa, Blephilia ciliata, Carex richardsonii, Geum triflorum, Houstonia longifolia, Oenothera serrulata, Panicum wilcoxianum, Potentilla pensylvanica bipinnatifida, Ranunculus rhomboideus, Sisyrinchium campestre, and Wulfenia bullii. Another variant of the dry prairie occurs on the dolomitic bedrock pavements exposed along our major rivers, particularly the lower Des Plaines; characteristic species are Actinea herbacea, Arenaria patula, Deschampsia caespitosa glauca, Muhlenbergia cuspidata, Petalostemum foliosum, and Scutellaria parvula.

A major variant of the dry prairie is the sand prairie, in which the principal fuel species is commonly Andropogon scoparius; in many respects it seems scarcely more than an exaggerated opening in the sand savanna. Characteristic species include Asclepias hirtella, Astragalus canadensis, Callirhoë triangulata, Carex muhlenbergii, Ceanothus herbaceus, Commelina erecta deamiana, Desmodium ciliare, Fimbristylis puberula, Orobanche fasciculata, and Sisyrinchium montanum. In moist to wet, acid sandy flats occurs an array of conservative species, many of them with affinities to the Coastal Plain. Such flats occur here and there throughout our southern and eastern sectors, off the moraines in the Lake Plain and in the Kankakee Sand Sections. Each such area has its own distinctive flora; characteristic conservative species in the aggregate include Aletris farinosa, Buchnera americana, Calopogon tuberosus, Carex alata, Carex atlantica, Cyperus dentatus, Eleocharis melanocarpa, Eleocharis microcarpa filiculmis, Hypericum adpressum, Hypericum canadense, Hypericum gymnanthum, Juncus biflorus, Juncus nodatus, Linum intercursum, Linum striatum, Ludwigia sphaerocarpa deamii, Lycopodium inundatum, Lycopus amplectens, Panicum polyanthes, Panicum verrucosum, Polygala cruciata aquilonia, Psilocarya scirpoides, Rhynchospora globularis recognita, Rhynchospora macrostachya, Rubus setosus, Salix lucida, Scirpus hallii, Scleria pauciflora caroliniana, Utricularia subulata, Viola primulifolia, Xyris difformis, and Xyris torta.

Ruderal Areas

It is presumed that many of our non-conservative native species developed their “weedy” tendencies in connection with the Native American peoples, particular those who were sedentary and agricultural. These plants are well adapted to soils regularly disturbed mechanically, subject to heavy trampling or compaction, or to very fertile soils free of conservative competition. In the drier soils such species include Acalypha rhomboidea, Agrostis hyemalis, Amaranthus hybridus, Ambrosia artemisiifolia elatior, Aristida aligantha, Asclepias syriaca, Asclepias verticillata, Aster pilosus, Bidens vulgata, Brassica kaber, Carex blanda, Cenchrus longispinus, Convolvulus sepium, Cuscuta campestris, Equisetum arvense, Eragrostis pectinacea, Erigeron annuus, Erigeron canadensis, Euphorbia maculata, Euphorbia supina, Galium aparine, Geum canadense, Juncus tenuis, Lepidium virginicum, Muhlenbergia schreberi, Oenothera biennis, Oxalis europaea, Oxalis stricta, Panicum capillare, Physalis subglabrata, Phytolacca americana, Plantago aristata, Plantago rugelii, Plantago virginica, Polygonum achoreum, Polygonum buxiforme, Polygonum scandens, Potentilla norvegica, Rhus glabra, Rhus typhina, Rudbeckia hirta, Silene antirrhina, Solanum americanum, Solidago altissima, Solidago canadensis, Sporobolus vaginiflorus, Verbena bracteata, and Veronica peregrina. Plants of moister or wetter ruderal ground include Acer negundo, Acer saccharmum Acnida altissima, Alopecurus carolinianus, Ambrosia trifida, Bidens frondosa, Cornus racemosa, Cyperus esculentus, Cyperus strigosus, Echinochloa crusgalli, Panicum dichotomiflorum, Polygonum lapathifolium, Polygonum pensylvanicum, Ranunculus abortivus, Rumex maritimus fueginus, Salix interior, Sambucus canadensis, Typha angustifolia, and Typha latifolia.

Boreal and Coastal Plain Relicts

An interesting aspect of the Chicago region is its position at the southern end of Lake Michigan with its Lake Plain flora, coupled with the large sand district associated with the Kankakee River. Together these singular areas have provided a remarkable context for habitats that support species otherwise more common northward or with their principal range in the Atlantic Coastal Plain. Many of these plants and their habitats, especially those which occur in the Indiana dune region, are discussed at length by Wilhelm.13

Those plants with an affinity for the Coastal Plain include Ammophila breviligulata, Aristida tuberculosa, Bartonia virginica, Bidens discoidea, Cakile edentula, Carex alata, Carex albolutescens, Carex debilis, Carex longii, Carex seorsa, Cirsium pitcheri, Cladium mariscoides, Decodon verticillatus, Drosera intermedia, Drosera rotundifolia, Eleocharis olivacea, Eleocharis equisetoides, Eleocharis geniculata, Eleocharis melanocarpa, Eleocharis microcarpa filiculmis, Eleocharis robbinsii, Eriocaulon septangulare, Euphorbia polygonifolia, Fimbristylis drummondii, Fuirena pumila, Gratiola aurea, Hudsonia tomentosa, Hydrocotyle umbellata, Hypericum virginicum, Juncus balticus littoralis, Juncus militaris, Juncus pelocarpus, Juncus scirpoides, Lathyrus japonicus glaber, Lechea pulchella, Linum striatum, Ludwigia sphaerocarpadeamii, Lycopodium inundatum, Panicum lucidum, Panicumoligosanthes, Panicum spretum, Panicum verrucosum, Peltandra virginica, Polygala cruciata aquilonia, Polygonella articulata, Polygonum careyi, Polygonum opelousanum adenocalyx, Potamogeton pulcher, Psilocarya nitens, Psilocarya scirpoides, Rhexia virginica, Rhynchospora alba, Rhynchospora globularis recognita, Rhynchospora macrostachya, Scirpus purshianus, Scleria reticularis, Sisyrinchium atlanticum, Solidago tenuifolia, Stachys hyssopifolia, Utricularia cornuta, Utricularia geminiscapa, Utricularia gibba, Utricularia inflata minor, Utricularia purpurea, Utricularia resupinata, Utricularia subulata, Viola primulifolia, Woodwardia virginica, Xyris difformis, and Xyris torta.

Plants believed to be relicts of a more boreal flora include Andromeda glaucophylla, Arctostaphylos uva-ursi coactilis, Betula alleghaniensis, Betula papyrifera, Betula populifolia, Betula pumila, Calla palustris, Campanula rotundifolia, Carex eburnea, Chamaedaphne calyculata angustifolia, Circaea alpina, Comptonia peregrina, Coptis groenlandica, Cornus rugosa, Cypripedium reginae, Diervilla lonicera, Epigaea repens, Glyceria borealis, Habenaria clavellata, Habenaria hyperborea huronensis, Juniperus communis, Linnaea borealis americana, Maianthemum canadense, Myosotis laxa, Panax trifolius, Pinus banksiana, Pinus strobus, Poa paludigena, Polygala paucifolia, Potentilla fruticosa, Pyrola elliptica, Pyrola rotundifolia americana, Rhamnus alnifolia, Salix candida, Salix syrticola, Spiranthes lucida, Thuja occidentalis, Trientalis borealis, Vaccinium macrocarpon, and Vaccinium oxycoccos.

-

Swink, F., Wilhelm, G. (1994). Plants of the Chicago region; a check list of the vascular flora of the Chicago region with notes on local distribution and ecology. Lisle, Ill.: Published by Morton Arboretum ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Homoya M.A., Abrell, D.B., Aldrich, J.R., Post, T.W. (1985). The Natural Regions of Indiana. Proc. Ind. Acad. Sci. 94, 245-268 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Schwegman, J.E. (1973). “Comprehensive plan for the Illinois nature preserve system. Part 2: the natural divisions of Illinois.” Rockford, Ill.: Published by the Illinois Nature Preserves Commission. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Albert, D.A., Denton, S.R., Barnes, B.V. (1986). Regional landscape ecosystems of Michigan. University of Michigan, School of Natural Resources ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Albert (in press) ↩︎

-

Hole & Germain (in press) ↩︎

-

Ellsworth, H.L. (1837). Illinois in 1837. Philadelphia: Published by S. Augustus Mitchell, and by Grigg and Elliot. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Brown, S.R. (1817). The western gazetteer; or emigrant’s directory, containing a geographical description of the western states and territories… Auburn, N.Y.: Published by H.C. Southwick. ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Parker, A.A. (1835). Trip to the West and Texas. Concord, Mass.: Published by White and Fisher. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Pratt, H.E. (1835). John Dean Caton’s reminiscences of Chicago in 1833 and 1834. J. Ill. State Hist. Soc. 28(1), 5-25 ↩︎

-

Coffinberry, S.C. (1880). Incidents connected with the first settlement of Nottawa-Sippi Prairie in St. Joseph County. Mich. Pioneer Hist. Coll. 2:489-501 ↩︎

-

Eleven percent of our native species have C values from 0-3, 89% from 4-10. ↩︎

-

Wilhelm, G.S. (1990). Special vegetation of the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore Research Program, Report 90-02. Published by the National Park Service. ↩︎