Early Alaska Transportation

by Alfred Hulse Brooks

The period of evolution from man-carried burdens to railroad transport, from raft and dugout to steamboat, is coextensive with the advance of man from savagery to civilization, a period to be measured by many thousands of years. In Alaska, however, the most primitive modes of transport are often found side by side with the most highly developed: the prospector leaving a railroad coach and shouldering his heavy pack becomes a beast of burden, as was the man of the stone age; the tourist may photograph from comfortable steamers the little bark canoe of the Yukon native; a modern ocean steamer anchored at Nome will be visited by the primitive skin boats of the Eskimo.

Less than two decades ago, no Alaskan valleys had echoed in the whistle of the locomotive, and a score of its navigable rivers had never felt the rhythmic chug of the steamer. Now1 there are over seven hundred miles of railroad in the Territory, and some form of steamboat service is found on nearly all Alaskan rivers. Of the tens of thousands who essayed the heart-breaking task of dragging and carrying their supplies through the passages in the mountainous coastal barrier, there were probably few who could realize that within a few years it would be possible to reach the Yukon by rail in not-as-many days as they took months for the journey.

Transport is the very essence of frontier life. Progress of industry and settlement are absolutely controlled by the means of transport. The pioneer whose mission is to obtain or to harvest rich deposits of placer gold can, by hard labor, carry out his projects through means of transport of his own development. If, however, other resources are to be utilized, such as the fertility of the soil, beds of coal, deposits of copper and gold veins, and if permanent settlements are to be made and homes to be built, steamboats, railroads, and wagon roads must be provided.

While much the larger part of Alaska is still almost as inaccessible as it was in its earliest history, yet the railroads, the automobile roads already built, and the well-established steamer service have revolutionized the transport system. This fact, and this alone, has made possible the beginnings of a systematic industrial development of the Northland. The relative efficiency and approximate cost of the most important means of transport in Alaska are shown in the following table:

Relative Efficiency of Alaskan Means of Transport

| Type | Weight carried | Miles traveled in 24 hours | Approx. cost per ton mile | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Backpacking | 50 lbs. per man | 12 | $25.00 | Wages $7.50 per day. |

| Pack horse | 200 lbs. per horse | 12 | $12.00 | Based on actual charges. |

| Dog sled | 100 lbs. per dog | 15 | $2.50 | Based on actual charges. |

| Wagon road | 500 lbs. per horse | 20 | $0.60 | Two-horse team at $20 per day. |

| Railroad2 | 700 tons per train | 300 | $0.08 | Frontier railroad. |

| Canoe or poling boat | 1000 lbs. per boat | 20 | $1.50 | Two men, wages at $7.50 per day. |

| River steamers | 500 tons | 250 | $0.05 | Average of river steamer freight. |

Though the cost figures given in this table are only an approximation, yet they give a measure of the difficulties with which the pioneer who provides his own transport has to contend and show why large industrial advancement is only possible when modern means of transport are available. Historical evidence of this truth is also found in the evolution of Alaskan settlement and industry. Until the Klondike gold was discovered in the 1890s, the only settlements in Alaska of any importance were at tidewater. The great interior contained only a few roving prospectors, and a dozen trading posts on the Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers were the only permanent settlements. The extraordinarily rich gold deposits of the Klondike and later those of Fairbanks, Nome, and other camps, made possible certain industrial advancements, but these constituted no permanent prosperity. It is only the construction of railroads and wagon roads which has led to the development of the resources of inland regions other than the rich placers.

Commercial shipping

When we took over Alaska from Russia, commerce, as has been previously pointed out, was confined to that of the fur trader along the coast and the lower courses of the Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers. The coastal settlements were served by a few smaller steamers, and extraneous commerce was by sailing vessels chiefly operating between Sitka and Petropavlovsk on the east shore of Kamchatka. Once a year, a ship arrived direct from Kronstadt on the Baltic. The few overland journeys of the Russians were by dog teams, and traffic on the rivers was by skin boats or scows.

The steamers carrying the Commission and the troops to Alaska in 1867 were among the first ocean steamers to be seen in these waters.3 At this time, the steamer John L. Stephens also made her first voyage from San Francisco to Sitka. This inaugurated a monthly service which was the only communication with Alaska for twenty years, when a semi-monthly service was begun.4 These vessels ran from San Francisco to Sitka and Wrangell, with occasional stops at other settlements in Southeastern Alaska. After 1871, when the Cassiar gold discovery of British Columbia was made, a field which was reached by the Stikine River route, the Wrangell call be came the most important, for this city was then the industrial center of Alaska. It could also be reached by a small vessel operated by the Hudson Bay Company which gave an intermittent service between Victoria and Wrangell.

For over twenty years, the traveler who wished to go beyond Sitka had to rely on the occasional vessels of the Revenue Cutter Service or the fur companies, or on the small craft of the fisherman and the small trader, for there was no regular communication with other Alaskan ports. There was no mail service outside of Southeastern Alaska until 1891, when a contract was made to carry mail to Unalaska during the summer months.5 It fell to Alaska Commercial Company, which took over the fur trade of the Russian American Company and obtained the first lease on the Seal Islands, to establish communication with Alaskan ports other than those of Southeastern Alaska. The company posts on Cook Inlet, Kodiak, Unalaska, and Saint Michael were reached by vessels running to San Francisco. At first, small steam schooners were used, later vessels of a thousand tons or more, Early in the ’70s, a more or less regular communication was established with the principal ports, later developing into a regular carrier service. By 1879, the steamer St. Paul was making a seasonal call at Saint Michael, ant the famous little steamer Dora was supplying the ports on the Aleutian and Pribilof islands. Later, the steamers running to Kodiak and Saint Michael became public carriers, and the same was true of the river steamers on the Yukon.

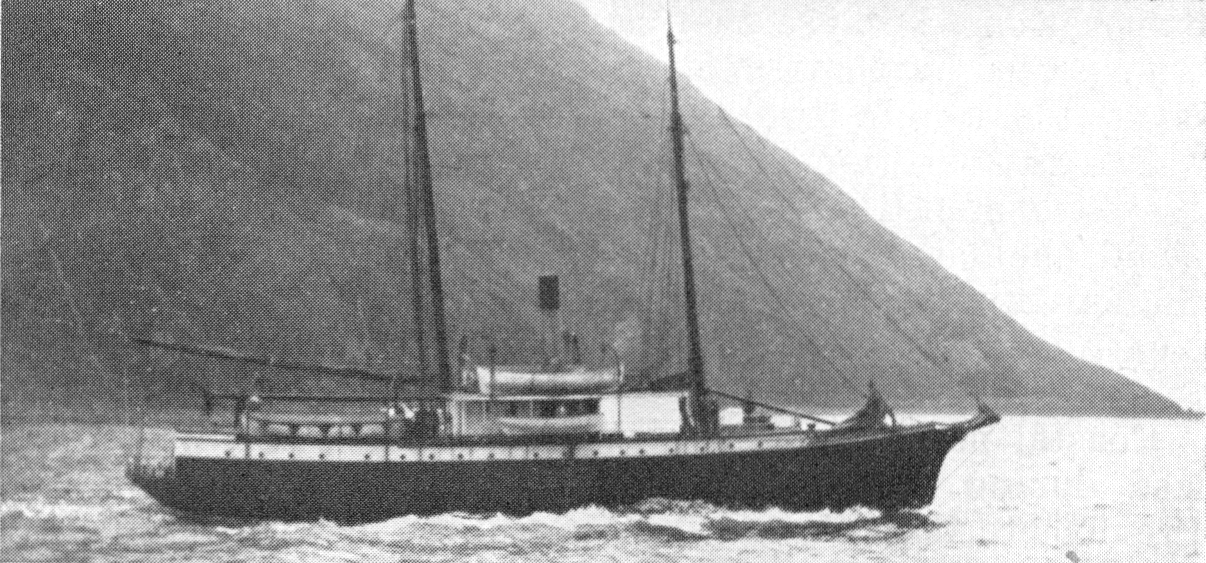

The Dora is perhaps the most famous of Alaska’s vessels, and has a record of forty years of service. At different times, she has served as a poacher of seal on the high seas, as a transport for furs and supplies, as a passenger boat, and finally as a fish boat. Originally built as a brig, she was later given steam power and for years plowed the dangerous waters of the Bering Sea. From 1891 to 1900, the Dora plied between Sitka and the ports to the westward as far as Unalaska. In 1900, she carried the local traffic from Saint Michael to Nome and other settlements along the southern coast of the Bering Sea. Later, for many years, she was the mail boat between Seward and Alaska Peninsula ports. The Dora, in spite of her great age, was always a staunch sea craft and weathered many a fierce gale that carried her hither and yon, for she had little steam power. She has perhaps the record for carrying more passengers with more discomfort than any vessel which ever reached Alaskan waters.

Though the reaching of Alaskan ports in the early history of the Territory presented many vexations, delays, and difficulties, these were the least of the transportation obstacles met with by the pioneer. Once landed with his outfit, he had to make further progress entirely on his own efforts. It was then a question of packing his supplies on his back, building his own boat—or, where conditions favored, making use of dog teams.

Sleds

Countless generations of Alaskan natives have used the dog for transport, and he is to Alaska what the yak is to India, or the llama to Peru. The climatic and topographic features of the Pacific seaboard are not favorable to sledding: the winter snows do not last long enough; and the heavy timbers and steep slopes also make the use of dog teams impractical. But the gently rolling upland region of the interior with its broad flat valleys and lack of thick timber furnished admirable sleigh routes, especially over the smooth surfaces of the many watercourses. The long cold winters also favored sled transportation, the season extending from November to May. The snowfall seldom exceeds three feet, but it remains continuous all winter, a fact which also favored the use of sleds.

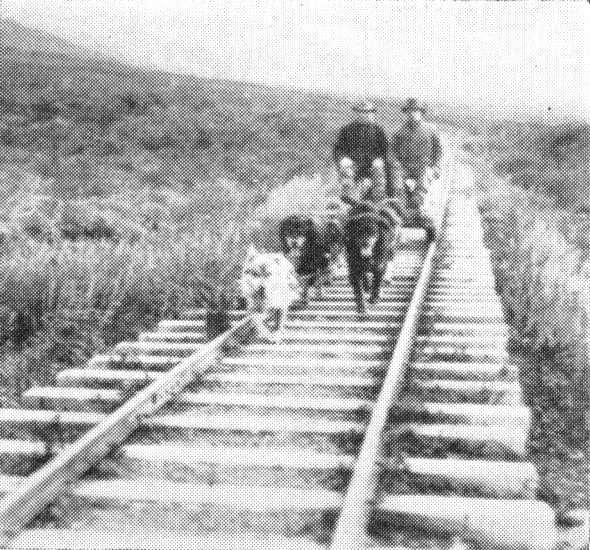

Hand sleds have been used as well as dog sleds, and many a gold seeker dragged his heavy sled for hundreds of miles. From 150 to 200 pounds is all a man can pull over an average trail. But in sledding over river or lake ice, he can take advantage of fair winds by employing improvised sails of the type used on the upper Yukon during the Klondike rush. The dog sled is, however, the typical mode of transport in inland Alaska as well as for the tundra region of the Bering Sea and Arctic Ocean. Originally there were two rather sharply differentiated types of sled dogs in Alaska: the malamute or Eskimo dog, and the “husky” or dog introduced from the Mackenzie valley, probably by the Hudson Bay traders.

Dogs

The malamute, originally the sled dog of the Bering Sea and Arctic coastal region, is now widely distributed in the Interior. The same family of dogs is found along the entire Arctic coast of Canada and in Greenland, and has provided the power for most of the sleds of the Arctic explorers. Their short, stocky build, their strong shoulders, their pointed ears and noses, and their gracefully arched tails are familiar to all through the illustrations in narratives of polar adventure. A good-sized malamute will weigh 75 or 80 pounds. The malamute varies in color from almost snow white to black, gray, and mottled.

The husky has longer legs and body than the malamute, is loosely built, and has a dense though shorter coat of fur. His resemblance to a timber wolf is very strong, and he appears to be a much more powerful animal than the malamute. He is more vicious too, but he is nevertheless perhaps the favorite sled dog, especially in the heavy freighting of the interior.

The Yukon Indians also had a dog on the first coming of the white man. It resembled the malamute but was smaller and not so powerful. These dogs, generally called siwash, are probably the degenerate offspring of the coastal malamute; and generations of underfeeding and abuse have produced an inferior breed. It is probable that the Athabaskans, the true Indians of the interior, got their first knowledge of sled dogs from the Eskimo.

The pure breeds of both malamute and husky are rapidly disappearing along the well-traveled routes by the inbreeding of native with imported stock. Many drivers prefer these cross-breed dogs, the offspring of native dogs and collies, setters, pointers, spaniels, Newfoundlands, and Saint Bernards. The pure-bred imported dogs, while more intelligent and tractable than the native animals, have not their endurance and resistance. One of the great faults is the tenderness of their feet on a rough trail. Some of the half-breeds, however, combine the endurance of their native blood with the intelligence and gentleness of their imported ancestors, and these make the most valuable draft animals. A common practice is to use an outside dog as the intelligent leader of a team of more hardy native dogs. The leader controlled by the commands of the driver, guides the dogs that follow.

Dried salmon is the standard dog food throughout Alaska. It is surprising how much work a dog can perform on a pound and a half of salmon a day. Large dogs engaged in continuous travel should, however, receive from two and a half to three pounds of food a day. They show the greatest endurance when fed a diet of fish and a cereal, such as rice or oatmeal, and bacon or lard at a ratio of 1:1½; and the best practice is to cook all the food, which, of course, is necessary for the cereal. Dogs are fed only at night, no morning or noon meal being provided. Most of the Indian dogs, and indeed many of those owned by whites, in summer are much undernourished. This makes them most arrant thieves, and every cache of provisions must by carefully barricaded against dogs. Even well-fed sled dogs are not to be trusted and will devour or destroy footwear and even their own harness. The native dogs require no housing in the coldest winter weather and, after being fed, will curl up and sleep in the snow, even though a blizzard be howling. Their shaggy skins are proof against the mosquito, ever present in the summer, but these insects sometimes torture them by stings about the eyes and nose.

There is no standard size for an Alaskan dog team. A prospector may drag a sled loaded with his 200 or 300 pounds of supplies with the aid of a single dog, or a driver may have a team of nine dogs or more. A driving team, however, usually includes not less than five or not more than nine dogs. Much larger teams are sometimes used for heavy freight. There is a known instance of dogs being used for hauling the heavy steel shaft of a gold dredge from Knik, at the head of Cook Inlet, to the Idiatarod district, a distance of nearly five hundred miles; the route led over a mountain pass in the heart of the Alaska Range and, though the journey was performed under great difficulties, the trip was completed successfully.

Sled dogs are hitched both tandem and in pairs, with an extra leader. For tandem driving, traces are used, and the rig is not unlike that for horses. In pair driving, the traces of each dog are merely hitched to a single tow line. If the dogs are staggered along the tow line, the team can adjust itself to any width of trail. The fan-shaped rig of Greenland, by which each dog is attached to the sled by a separate tow line and the team spreads out radially, is not adapted to narrow trails and is unknown in Alaska. Each dog is fitted with a padded leather collar from which his traces reach back and are attached to the tow line.

Distance of a day’s trail for a dog team and weight pulled vary so much, depending on condition of trail, on gradient of course, and on weight and endurance of dogs, that it is difficult to generalize. Where a new trail is being broken and where there are steep gradients, 50 pounds to the dog is an ample load. Indeed, in some cross-country journeys, this load may have to be reduced to 30 or 40 pounds. On the other hand, over a smooth, hard, level trail, strong dogs have been known to drag as much as 300 pounds. It is probably safe to say that a good dog on hard, level trails should haul 100 pounds—that is, about 25 percent more than his own weight. this load he will not take over 15 or 20 miles a day. Reduce this weight to 50 pounds, and the dog should make 25 miles a day. The famous dog races at Nome have shown that a dog team hauling only the empty sled can average nearly 90 miles a day for five days.6 The winter mail contracts call, on the average, for a speed of 22 miles a day; but the carriers frequently exceed this, runs of over 40 miles a day having been recorded. The mail carriers haul from 50 to 75 pounds of weight per dog.

Many long journeys have been made over well-beaten trails by good “dog mushers” where a day’s average travel was 25 miles. This, however, is hard work for the driver as well as the dogs. The driver seldom rides on the sled, except on down grades, but runs behind, guiding and steadying it by the handle bars. Where a new trail has to be broken through new snow, a man on snowshoes goes in advance of the team.

The dog sleds are 8–12 feet long and about 20–24 inches wide. They are strong, built of hickory or oak, and made not too rigid. A certain looseness and pliability allow the runners to follow the tracks. Small sleds weigh about 75 pounds, large ones nearly 200. For freighting, flat sleds are used, sometimes with a “gee pole” for guiding at the front where the driver helps haul the load, sometimes with the gee pole at the rear. Travel sleds are made with a basked superstructure and two handles at the rear. These are used by the driver to guide the sled, and when opportunity offers he steps on the rear of the sled for short rides.

Dogs are also used in summer to a limited extent as pack animals by both Eskimo and Indian, and occasionally a lone prospector will be found to make a similar use of them. A dog will pack 20 or 30, even 40 pounds. Unless thoroughly broken, these dogs are difficult to control, and one of their favorite tricks is to lie down in water, pack and all.

Backpacking is the most primitive and laborious mode of transport and is resorted to only when all other means fail. As an actual means of forwarding supplies, it is used only between navigable waters, namely on portages. A portage is chosen, so far as circumstances permit, so as to afford firm footing and easy grades. The Chilkoot Pass is the most famous portage in the world, for thousands of tons of supplies have been carried across it. It lies some twenty miles from, and 3,100 feet above, tidewater; and, as has been indicated earlier, the approach to it, though easy enough at first, becomes steep and difficult. To the place called the Scales, sledding was feasible; but from here on, a steep climb to the summit has to be made, and transport was on the backs of men. This portage provided the test that winnowed out the strong from the weak, the stout-hearted from the failures. The average man found, at least at the start, that 50 pounds was a heavy load up the steep ascent; many learned later to carry 100 pounds, though such a burden was a serious strain on the heart, and some whose determination was greater than their strength succumbed under it. Over an ordinary portage with hard trail and no grade, most physically strong men will carry 100 pounds; and experienced packers will take 150 or even 200 pounds on a cross-country trip, through the hills and mountains. But relatively few will carry more than 50 pounds, and that amount not over fifteen miles a day.

Horses

In the Pacific seaboard region of Alaska, the best grasslands are along the shores of Cook Inlet, on the Alaska Peninsula, and on Kodiak Island. But these areas are by no means all the grazing lands, and grass is sufficiently abundant elsewhere to make the use of horses feasible for summer journeys. There is much good pasturage in the Susitna valley, especially on its western margin in the Yentna River basin. The Copper River has less grazing land in its basin, but it suffices for the traveler. Summer pastures sufficient for pack train are widely distributed in the great inland region beyond the Pacific ranges and northward as far as the Arctic Mountains which divide the Yukon waters from those flowing northward into the Arctic Ocean. Some splendid grasslands are found in this region, for example along the Tanana and its tributaries. In other places again, such as north of the Yukon, the grass is scant, but patches sufficient for a pack train can usually be found at distances not exceeding a day’s march. Horses have been used by the Geological Survey as far north as the Arctic divide, and the International Boundary Commission took a pack train all the way to the Arctic Ocean along the 141st meridian, north of the Porcupine River. As the Bering Sea is approached, nutritious grass becomes scanter and is confined chiefly to the highlands, the extensive lowlands being chiefly covered with moss and marsh grass. In this region, only careful planning and search for pasture will permit the use of pack horses. Much the same is true of Seward Peninsula, though the Geological Survey expeditions have traversed its entire area with pack trains. There is some grassland even in the Arctic Slope region of Alaska, but not in sufficient abundance to make long pack train trips feasible. It is probably safe to estimate that there are in Alaska some 300,000 square miles in which the grass is sufficiently abundant to permit the use of a pack train.

Horses were brought to the Yukon as early as 1885, but they were relatively little used until the Klondike rush. The first long pack train trip in Alaska was that made in 1891 by E. J. Glave and Jack Dalton when they went from the coast into the Lake Kluane region, previously discussed in Chapter 16.7 The Army exploration of 1898 were made in part with pack horses, and in 1899 the Geological Survey first used horses. That summer, W. J. Peters and I made the journey from Haines in Southeastern Alaska to Eagle on the Yukon, a distance of nearly six hundred miles, that has already been referred to in Chapter 16. In 1902, I made what is perhaps the longest pack horse journey ever accomplished in Alaska: from Cook Inlet, round the base of Mount McKinley, and on to the Yukon at Rampart. In 105 days, the pack train traveled some 800 miles with the personnel going entirely on foot. At the start, the horses were each loaded with 250 pound sacks; but, as provisions were consumed at the rate of about 21 pounds a day, the packs gradually became lighter. On the other hand, some of the least strong of the horses were so weakened by the arduous trail and by the insect pest that they had to be shot before the journey was half over; at the end of the trip only nine of the original 20 animals remained.

During such journeys the animals find their food in the native grasses which are very nourishing. There is in Alaska, however, no natural curing of grasses such as takes place in the arid states of the West. When frost comes, about the middle of September, the horse feed is practically ruined. Therefore, the use of pack horses in Alaska is pretty much limited to the season from June 1 to the middle of September. By feeding grain one can considerably extend the season, but as a horse will eat up his own load in ten or fifteen days, such use is impractical for long journeys.

Horse sleds, like pack animals, only came into general use after the Klondike discovery. Their efficient use is limited to roads which must be at least passable after the winter snow comes. In the early days there was much horse sledding over the ice of the Yukon and other rivers. But even this implies the breaking of a trail, and the use of horse sleds is now limited to established winter roads. Before good sled roads were available, many so-called “double enders” were in use. These are small sleds, not unlike the freight sleds pulled by dogs, that are drawn by a single horse or by two driven tandem.

Before trails passable for sleds were established, a mode of transport called raw hiding was sometimes resorted to. In this, freight was securely lashed into bales which were encased in raw hides, to which the traces of horses were attached. Such bales could be dragged over any trail, and even over bare ground, on which the horse could find footing, for it was of no importance which side of the load was on top. It was, of course, on account of the friction, a very inefficient use of horse power and little, if any, improvement over the back load. Now, where roads have been built or other good sledding conditions are found, winter horse freighting is by the familiar double- or bobsled, known in all the northern states.

Reindeer

During the early years of the introduction of reindeer into Alaska much was said about their use for transport. It was pointed out that the advantages of the reindeer over the dog were that he found his own food, and could be used as pack animal in the summer and sled puller in the winter. The enormous use of reindeer transport in Siberia appeared fully to justify these contentions; yet after thirty years of reindeer breeding in Alaska, their use in transport is almost negligible. In Siberia, a sled load of 270–300 pounds is easily hauled for long distances by the reindeer. But these are the large Tungus animals which average at least a third larger than the Alaskan reindeer, are used as saddle animals, and will carry a rider even through deep, soft snow; as pack animals they will carry from 100 to 200 pounds. It is difficult to understand why a similar use in Alaska has met with such indifferent success. In the earlier days of the reindeer experiments Laplanders were chiefly used for training both the reindeer themselves and the Eskimos in their use. This was undoubtedly, as can now be seen, a mistake. The Laplander had both the ignorance and the lack of adaptability to a new environment inherent to his semi-civilized state. He was dealing with a Siberian animal much wilder than the more highly domesticated one of his own land. The small pulka, or Lapland sled, fashioned out of half a log and rounded at the bottom, while making a good passenger vehicle, was not adapted to hauling freight; and the freight sled with runners was new to him. Moreover, in Lapland, the reindeer was chiefly used to carry men and light loads, and there was no use of the animal to transport heavy freight for long distances, such as had been done in Siberia for many generations. As a means of domesticating the Alaskan reindeer and of training the natives in their use, the Laplander was almost a complete failure.

Reindeer transport had, however, a more thorough test by some of the mail contractors. These men with a keen idea to business fully realized that if the reindeer could be substituted for dogs there would be a material profit in the change. The reindeer subsists on food of his own finding, and it costs $75 to $100 a year to feed a dog. After a period of careful test by men who had the initiative of the frontiersman, the experiment of substituting reindeer for dogs as mail carriers was on all but a very few routes entirely abandoned.

There are some evident reasons why the reindeer could not be substituted for the dog. Most of the established dog team routes are along the large waterways, and in the great inland regions of Alaska the lichen or reindeer moss grows only on the highlands above the timber line. Obviously the sled reindeer could not be driven to the highlands to obtain its pasture. Local climatic conditions were also an obstacle. A thaw followed by a freeze might cover the pastures with ice and make the lichens unavailable to the reindeer. In contrast to this, the general use of dog teams made the furnishing of dried salmon for dog feed a well-established industry along the watercourses. The reindeer will eat little except its regular food of lichens, but the dog is omnivorous in its appetite. It should be added, however, that the great tundra areas of the Bering Sea and of northern Alaska are the natural home of the reindeer. The barren ground region has as yet but little population save for the native whose mode of life has long been adapted to the use of dogs. Hence the substitution of the reindeer can only be brought about very gradually; the change of a people from a nomadic to a pastoral life must be a work of generation.

The following description by Jarvis illustrates the use of reindeer as sled animals:

All hands must be ready at the same time when starting a deer train, for, just as soon as the animals of the head team start, they are all off with a jump, and for a short time keep up a very high rate of speed. If one is not quick in jumping and holding on to his sled, he is likely either to lose his team or be dragged along in the snow. They soon come down to a moderate gait, however, and finally drop into a walk when tired. They are harnessed with a well-fitting collar of two flat pieces of wood, from which a trace goes back on each side to the ends of a breast or single tree that fits under the body. From the center of this a single trace runs back to the sled either between or to one side of the hind legs. In the wake of the legs this trace is protected with soft fur, or the skin will soon be worn through with the constant chafing. Generally, there is a single line made fast to the left side of a halter and with this the animal is to be guided and held in check; but this line must be kept slack and on only when the deer is to be guided or stopped. By pulling hard on this line, the weight of the sled comes on the head and the animal is soon brought to a standstill, though often this is only accomplished after he has gone in a circle several times and you and the sleds are in a general mix-up. No whip is used and none should be, for the deer are very timid and easily frightened and once gotten in that state are hard to quiet and control. A little tugging on the lines will generally start them off even when they balk. The sleds in use are very low and wide with very broad runners.8

During the past decade much advance has been made in the training of sled deer by the Eskimo, mainly because of the supervision and encouragement of W. T. Lopp and his assistants of the Alaska Reindeer Service. The use of sled deer is gradually becoming a part of the industrial life of the Eskimo, and the more intelligent herders are shoring an increasing facility in handling them. The superintendents of the Alaska Native School and the Reindeer Service are making much use of reindeer in their winter journeys of inspection. The journeys of one winter using reindeer aggregated 1,300 miles, and the average normal day’s travel was 28 miles. It is also worthy of note that native reindeer races have established a record of ten miles in 27 minutes, 20 seconds and that the pulling capacity of a single deer is 1,600 pounds for a distance of 250 yards. A sled reindeer should make 25 miles a day for a journey of 100 miles or so, hauling the driver and 50 or 75 pounds, perhaps 300 pounds in all. The reindeer tire easily in soft snow and must then be frequently rested.

The argument for the use of reindeer is presented by Carl O. Lind of the Alaska Reindeer Service:

Our trip, which demanded 45 days for its accomplishment, was successfully done before Christmas. In all we traveled about 1,000 miles under adverse conditions, and four out of seven deer made the return trip without us, hauling 100 to 200 pounds. If dogs had been used they could not have hauled their own provisions being picked up by themselves whenever we stopped. No shelter was needed. When the most furious wind sweeps its path, the deer simple faces it with an open mouth and with an expression of satisfaction and joy… It goes uphill and downhill alike. Trail or no trail, it will haul its 200 pounds or more day after day; yes, week after week.9

The argument against the use of reindeer has been presented by the late Archdeacon Stuck:

There is not a dog less in Alaska because of the reindeer… Speaking broadly, the reindeer is a stupid, unwieldy, intractable brute, not comparing a moment with the dog in intelligence or adaptability… The rein with which he is driven is a rope tied around one of his horns. He has no cognizance of “gee” and “haw,” nor of any other vocal direction, but must be yanked hither and thither with the rope by main force; while to stop him in his mad career once he is started it is often necessary to throw him with the rope.10

Some use of the Alaskan reindeer as pack animals has been made, but this mode of employment is not yet well developed. The large Siberian reindeer will carry 100–150 pounds, but the smaller animal of Alaska will on the average probably not carry over 50 pounds. The burden is carried in cloth hampers hung over the animals and made secure by a lashing going over the back and around the animal’s belly. Unless thoroughly broken, the pack-bearing animal must be led. There appears to be no question that the pack reindeer will find a use in the tundra regions where there is not enough grass to support horses. Its employment on long journeys has not been tested. Difficulties of herding when the deer are in pasture present themselves, and as yet but few reindeer have been broken to the pack.

The evidence in hand shows that the Eskimo reindeer has clearly demonstrated the fact of the utility of the sled reindeer to his mode of life. For his purpose the deer is no doubt more suitable than the dog, for his life is spent in the tundra region, where reindeer pastures are usually abundant. On the other hand, experience up to the present has shown that the needs of winter transport for the whites can better be served by the dog and the horse than by the reindeer. As has already be suggested, the value of the reindeer to both native and white as a source of meat and hides has been fully demonstrated.

It is roughly estimated that about 480,000 square miles of Alaska’s area are, by virtue of the physical condition, suited for winter dog transport. Of this area, about 220,000 square miles, or less than half, have the physical condition that makes the use of reindeer practical. This gives a rough measure of the relative value of the two draft animals; yet, as has been shown, there are other factors which must be given consideration in making this comparison.

Water transport

Water transportation has been the savior of the province. Without Alaska’s enormous coast line, aggregating over twenty thousand miles, and her extensive river systems that give access, though in part only with great difficulties, to the most remote parts of the Territory, industrial advancement would have been impossible. The Alaskan Yukon and Kuskokwim basins include upwards of five thousand miles of waters navigable for river steamers. It is these great arteries of commerce that have served chiefly in the past to open up the interior to settlement.

Hand-powered craft

Long before any steamers had navigated these rivers, these waters had been much used for transportation in various ways. The inland natives of Alaska were, it is true, a land folk who made relatively little use of the rivers. Their only boat was a small bark canoe, too frail and light to be used for transport. Downstream journeys were made by crude rafts and occasionally by a hastily improvised skin boat made by the stretching of the hide of a moose or caribou over an ill-constructed framework. They had, however, no means of transportation upstream, except the frail canoes which could be pushed against only a slight current. As has already been shown, the Russians were indifferent boatmen, and their clumsy river craft were but ill-adapted to upstream navigation. the first good river boats in Alaska were those introduced by the Hudson Bay voyageurs whose boats included both the double pointed bateaux, using both oars and poles as water power, and the bark canoes.

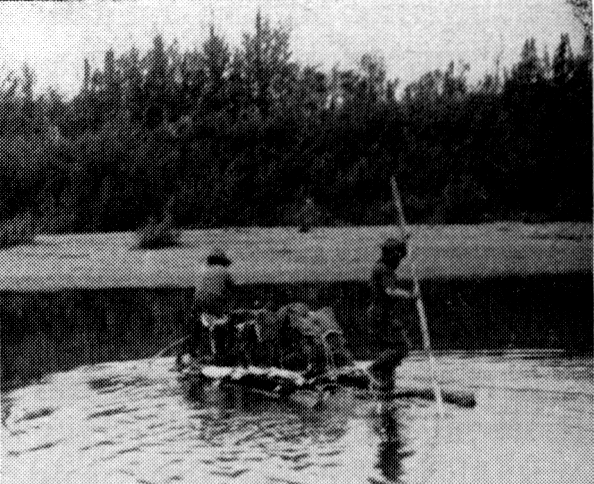

There were, as has been previously pointed out, no trees on the Yukon large enough for dugouts and, because of the small size of the white or canoe birch trees, no possibility for making practical large bark canoes. Therefore, the Yukon pioneers were forced to provide boats built of whipsawed lumber. This common type was a flat-bottomed boat, sharply pointed at the bow and with a rather narrow stern, of the general type of a dory, and some 18–24 feet long. Later the Yukon poling boat was devised. This was a long, narrow, tapering craft, admirably adapted to upstream journeys, against swift current and in shallow water. The poling boat was 20–30 feet long, and amidships, its bottom measured from 12 to 20 inches with tapering sides, giving it 2½–3 feet of beam at the gunwale. Though tapering rapidly at both ends, it is usually built with snub nose at both bow and stern. The Yukon poling boat was no doubt an adaptation of similar types of craft long used on the western rivers. Up to the time of the use of steamers, the Ohio River keelboats, said to have been first used in 1793, with their expert polers were the only crafts which would go upstream. These Ohio River boats were 50 feet long, but only 12–15 feet wide, and were propelled by ten polemen. Their form and mode of use were identical with the Mississippi craft.

It is surprising with what facility good polemen can push a loaded boat of this type up swift streams and with barely enough depth of water to float the craft. With fair conditions two good men could take a ton of supplies upstream at the rate of 10–20 miles a day, and with a lighter load. 30 miles a day were not uncommon. In the early days of Yukon mining it was not infrequent for a party of men to make the journey from Fortymile to Lake Lindeman, the head of boat navigation, a distance of nearly 600 miles, in a month, an average speed of nearly 20 miles a day. This included the time spent in making the difficult portage around White Horse Rapids and Miles Canyon, and also the easy navigation of Laberge and other lakes of the upper Lewes River.

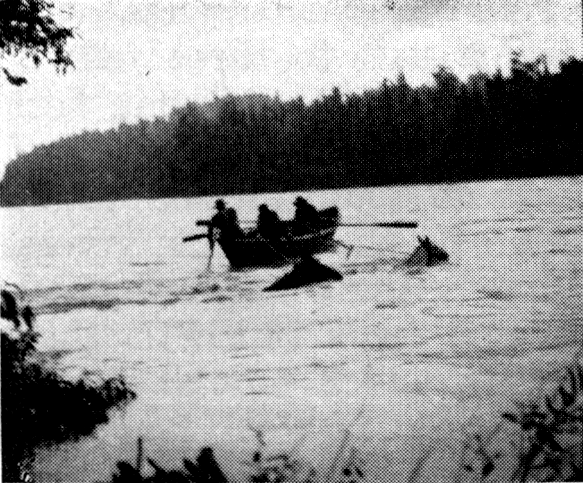

In these upstream journeys propulsion by poling was varied by tracking. This consisted in dragging the boat by lines of men walking on the shore. By attaching two lines to the boat, the men can readily steer it from the shore; and if good footing can be obtained, they can drag half a ton or more of supplies upstream at the rate of ten miles or more a day. Where the stream is shallow and the current swift, much wading is usually necessary to ease the boat over the bars. Where there are steep-cut banks and the water is too deep to pole, the boat must be pulled by the bushes and trees along the banks. This method of propulsion, formerly called “bushwhacking” on the Ohio River, is slow and tedious; and a whole day may be consumed to advance a few miles. It is not uncommon to use dogs as draft animals in taking boats up streams.

It was the Canadian explorers like William Ogilvie who first introduced the Peterborough canoes on the Yukon; and later, this craft was much used by the Northwest Mounted Police. Just as the poling boat has been the craft of the prospector, so the canoe has been the craft of the explorer. In general modeled after the Ojibwe bark canoe, the Peterborough is an admirable swift water boat, carries a large cargo, and is so light that it can be portaged a long distance. This model is built in sizes varying from 17 to 24 feet in length with a beam of 40–52 inches. The favorite canoe of the explorer is about 19 feet long and 46 inches wide. Such a boat built of cedar will, when dry, weigh about 120 pounds, and in an emergency can be packed by a single man across a portage. It will safely carry a cargo of half a ton besides a crew of two or three men. With a fair wind it makes a fairly good sailing craft. When it is equipped with six-foot paddles, ten-foot poles, and good tracking lines, there are no inland waters navigable to any other craft on which a Peterborough canoe can not be used. I have used a Peterborough provided with a small coaming and canvas air-tight compartments in fairly heavy weather on the Bering Sea. In river navigation, punctures by snags or rocks of thin cedar planking are not uncommon, but these are quickly and permanently repaired by strips carried for the purpose. The Geological Survey in the course of its explorations and investigations in Alaska has used these canoes on about fifteen thousand miles of the watercourses of Alaska. During the Klondike rush, when every type of craft was used, folding canoes and boats were not uncommon. Though easier to portage than Peterboroughs, they are useless for upstream work, being too flimsy to buck a current. They have found use in explorations, because they can be packed on a horse and transported overland and they are a necessity for cruising rivers too deep to ford, the banks of which are untimbered.

Engine-powered craft

The introduction of the light portable gas engine has greatly modified Alaskan water travel. Many prospectors avoid the labor of poling and tracking by its use. In shallow rivers air propellors have been successfully used. Nearly every Yukon Indian now has some sort of gas boat to visit his fish wheels and to travel from place to place.

Coastal navigation has also been completely revolutionized during the past two decades by the gas engines. Previous to 1900, the prospector and the fisherman traveled chiefly in crafts propelled by sail and oars, but now the use of power boats is almost universal. The favorite craft is the Columbia River fishing boat, 20–30 feet long, of the lifeboat type, and admirable for heavy weather. These, formerly propelled solely by sail and oars, are now equipped with economical heavyweight gas engines.

The Western Union Telegraph exploring expeditions had for part of their project the steam navigation of the Yukon River. Two flat-bottomed boats about 60 feet long, the Wilder and the Lizzie Horner, were shipped to Saint Michael in 1866, but neither succeeded in entering the mouth of the Yukon. Navigation of the Yukon continued by small boat until the newly organized Alaska Commercial Company brought in its first small steamer, the Yukon. This boat was 50 feet long with 12-foot beams, was equipped with two engines, and drew when loaded 18 inches of water; it was built by John W. Gates of San Francisco. On July 4, 1869, with Captain Benjamin Hall as master and John R. Forbes as engineer, the Yukon left Saint Michael and 27 days later arrived at Fort Yukon, having completed the first steam navigation of the lower thousand miles of the Yukon River. Within the next ten years, three other small steamers were brought to the Yukon and navigated the river up as far as Fort Selkirk,11 1,700 miles from the Bering Sea. These boats were chiefly used in the fur trade, but they also supplied the few prospectors then in the region.

With the influx of miners after the discovery of gold in the Fortymile district, a larger vessel was demanded. In 1889, the Alaska Commercial Company built the Arctic,12 140 feet in length with a 28-foot beam. By this time the annual freight taken up the Yukon was largely the trading goods and provisions to supply the Alaska Commercial Company posts. Freight charges to the upper river were $50 a ton, passenger rates $150. The freight rates were very reasonable, and the passenger rates affected but few of the miners, who arrived mostly by the Chilkoot Pass route. In 1892, the North American Trading and Transportation Company entered the Yukon as a rival in fur trade and transportation. Their first boat, the Portner B. Ware, of about the same size as the Arctic, ascended the Yukon for some 200 miles in September, but was frozen in before it reached the mining camps. The organization of this company was due to the energy of J. J. Healy, a pioneer Alaska fur trader. He long maintained a trading post at Dyea, the gateway of Chilkoot Pass, and from information obtained from the miners became convinced of the industrial importance of the Yukon. As the managing head of a great commercial company, he was a commanding figure on the Yukon during the Klondike days, but he died a pauper in 1910.

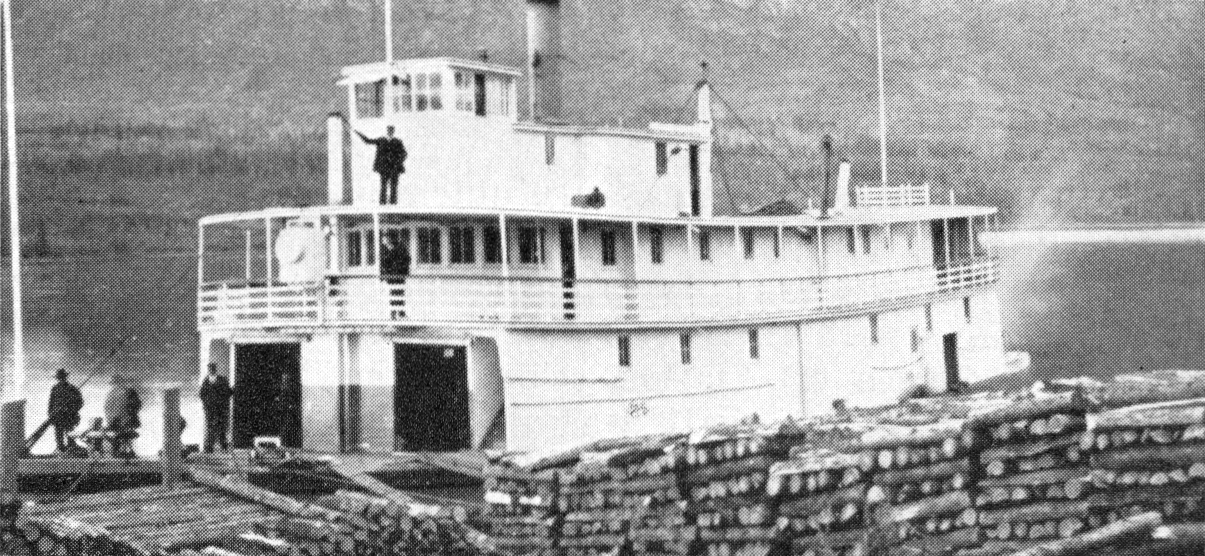

With the Klondike rush came an enormous expansion of Yukon River traffic. In 1898 and 1899, between 75 and 100 steam-driven vessels were plowing the muddy waters of the great river and its tributaries. In 1900, five transportation companies were operating 33 river boats on the Alaskan Yukon, and a dozen steamboats were navigating the Canadian waters above. There is no record of the traffic during the height of the Klondike travel; but in 1901, when it had greatly subsided, 35 boats carried 25,000 tons of freight up the Yukon, and the passenger traffic upstream and downstream aggregated 2,500 persons. This was at a time when the building of the White Pass & Yukon Railroad had, by establishing, a through freight and passenger service from Skagway, greatly reduced the traffic on the lower river. The tariffs were, in 1901, $85 a ton for freight and $125 a passenger, from Saint Michael to Dawson.

During this period, large packets were built for the Yukon service,13 comparable to those used on the Mississippi. Their masters and pilots were recruited from the Mississippi and Columbia rivermen, the former having the prestige of having operated large boats, the latter being more experienced in handling steamers in swift water. The large steamers had lengths of 222 feet, beams of 42 feet, depths of 6 feet, and horsepower of 1,000. For many years they were all wood burners, for the several attempts to use the local lignitic coal were unsuccessful.14 In 1906, many of the boats were changed to oil burners, the petroleum being brought from California. These large packets proved to be uneconomical, and there has been a gradual change to smaller boats of from 400 to 600 tons which could be efficiently used on the small tributaries of the Yukon. With the decrease of gold mining, steamer traffic has already decreased. In 1919, only nine steamers were operated in the Alaskan Yukon, carrying a total of less than 10,000 tons of freight.

In general, the Yukon is open to navigation from June until October. The ice-free season, however, varies in different parts of the basin. Above Dawson, the river is usually clear of ice soon after the middle of May, and steamers can be operated well into October. Navigation on the lower Yukon is possible from the last week in May until the end of September. The ice, however, often does not go out of the Yukon delta until July, and the river there may be frozen again by the middle of September. One reason for the high freight rate on the Yukon is that the expensive equipment and, to a certain extent, the personnel too are idle for eight to nine months in the year. All the profits must be made during the short season of navigation.

Roads

Nothing emphasizes the slow growth of means of transportation in Alaska more than the history of its road construction. The Russians during nearly a century of occupation built less than five miles of wagon road in the American possessions. During the next thirty years, up to the time of the Klondike gold discovery, we added barely another five miles to the total length of wagon road. At the fiftieth anniversary of the annexation of Alaska, there were only 980 miles of wagon road in the Territory,15 an area of nearly six hundred thousand square miles and a population then of nearly seventy thousand. At this time, the Government had spent a total of $3,970,000 on road and trail construction in local taxes. Alaska had in turn produced minerals, fish and fur up to a total value of $800,000,000. It is questionable whether any other one country in the world has shown such a notable industrial advancement with such a scant outlay of public funds for transportation facilities.16

Private construction

Photos by C. W. Wright.

A little construction and some improvements of roads at Sitka were done by the military authorities between 1867 and 1877, but beyond this bit, there was no building of roads until after the discovery of the Juneau gold. In 1882, a horse trail was built by the miners for two miles up Gold Creek, and later this was changed to a wagon road which, by 1888, had been extended into the Silver Bow basin. The building of this road in part through a steep-walled valley was an expensive undertaking and all of it was paid for by local mining industry. In 1898, a law was passed, authorizing the construction and maintenance of toll roads and bridges in Alaska,17 a privilege of which, however, few availed themselves. The Chilkat Indians had long regarded the Chilkoot Pass trail as a toll road owned by them, a monopoly which the pioneer miners soon disregarded and claimed the right of carrying their own burdens over it without charge. When the Klondike rush started, a wagon road was constructed from tidewater at Dyea for eight miles to the entrance of the canyon, and during the height of the travel it carried on a brisk business.

In the spring of 1898, George A. Bracket completed fifteen miles of wagon road from Skagway to the base of the final steep thousand-foot climb leading to the summit of the White Pass. This road traversed the heavily timbered flat of Skagway River for some five miles, and beyond led along the precipitous slopes of a rocky defile. At that time, the Bracket road was the longest and most difficult piece of highway construction that had been attempted in Alaska. Remnants of this pioneer road are still visible from the White Pass & Yukon Railroad where they can be seen clinging to the sides of precipitous cliffs. Bracket’s troubles, however, did not end with the building of the road, for he found it difficult to collect the toll of $20 a ton to which he was legally entitled. Many Klodikers could see no reason for paying toll on a route through which they had had a sled trail before the building of the road. Some of the toll collectors were roughly handled. But the controversy over toll was short-lived, for by May of 1898 the railroad surveyors had arrived and the railroad company bought the wagon road,18 both for the prevention of competition in the haulage of freight and for hauling use in construction.

Jack Dalton, in 1898, built a horse trail from Pyramid Harbor on Lynn Canal to the top of the pass at the head of Klehini River. This opened up a route into the interior well suited for horses and cattle which Dalton had explored. No trail work was necessary beyond the pass where the country was open. Dalton himself drove in several herd of beef cattle and horses, reaching the Yukon either at Five Finger Rapids or at Fort Selkirk at the mouth of the Pelly. The Dalton trail was the best pack horse route into the interior, but it was not much used even before the completion of the railroad and the venture was not a financial success.

In addition to the above, a few toll bridges have been built at various places in Alaska. On the whole, however, the toll road and bridge act of 1898 was entirely ineffective in opening up Alaska.

Public construction

In 1904, Congress made a second attempt to provide roads for Alaska without appropriating any funds. This effort compelled the United States commissioners to appoint a road overseer in each district, who was to receive the magnificent wage of $4 a day, the average wage at that time being $6 to $10 a day. Recognizing that the poor overseers would be at a financial loss for every day of employment, the law specified that they were to be paid for only ten days in the year. In this time these philanthropists were not only to construct roads but also to notify every man in their district that they must give two days’ work to road building each year, or in lieu thereof, to pay a head tax of $8. This law was evidently framed on the ancient statutes of many of the Eastern states, by which road building was made the duty of every citizen, and a knowledge of road engineering was recognized to be inborn in every American. For generations, this ancient fallacy hampered the development of good roads, and it was done away with only after the inauguration of modern highway construction.

No fault can be found with the principle of the Alaska Road Act of 1904, of throwing the burden of road construction on the Territory. But this should have been done by a proper system of local taxes, and the funds collected spent by qualified engineers. In Canadian territory, this was recognized from the start, and the royalty collected on the Klondike paid for the excellent system of highways in the Yukon Territory. The Alaskan law was almost futile in providing means of communication, though a few local sled roads and trails were improved, most of which were badly located and poorly constructed.

The extensive federal exploration of Alaska inaugurated in 1898, chiefly by the Geological Survey and, for the first few years, by the Army, included many long journeys. Many of these exploring expeditions used horses and, incidental to their advance, many miles of rough trail were established. These were subsequently followed by others and, in lieu of better trails, became established as routes of travel. A few are still in use, and we still hear of the Gem Trail, and the Survey and Army trails. Far more important than these trails to betterment of means of communication were the maps and reports which resulted from the work of these expeditions. All had as part of their mission the location of possible routes for wagon roads and railroads. The actual areal mapping fell chiefly to the Geological Survey which, before the epoch of road and railroad construction that began some five years later was inaugurated, had made contoured reconnaissance maps of nearly all the routes which were subsequently chosen or considered for wagon roads or railroads. This work admirably furnishes conclusive proof of the value of topographic maps. The cost of the areal topographic surveys of Alaska has been far less than it would have been had it been necessary to carry out explorations for every road and railroad project. These maps gave information on the best general route, and it was only necessary for the engineer to make his location survey.

Many of the reports of this exploring expedition made more or less definite recommendations for road and trail construction. For example, in 1903, incidental to the discussion of the future of placer mining,19 I recommended that a million dollars be spent in building wagon roads to the inland placer camps. The recommendation included a road from Valdez to Eagle or Fairbanks as a main highway and many other local roads. The opinion was then expressed that several of the Yukon gold camps had probably already spent more money in the transport of supplies than the cost of wagon roads. This was probably an exaggeration, but that such a generous project for wagon roads was sound is proved by the fact that most of those it included have, during the twenty years that have since elapsed, been completed or are under construction.20

Though the trails established by these early exploring expeditions were of use to the prospector, they were little more than cuts through the timber, with here and there some small bridges. The only actual trail construction by such an expedition was that built under the direction of Major W. R. Abercrombie, from Valdez inland. Abercrombie, commanding the Copper River expedition of the U.S. Army, landed at Valdez in the spring of 1898. His parties, as already noted in Chapter 16,7 subsequently made their way inland over the difficult an dangerous Valdez Glacier route and also explored other passes through the coastal mountain barrier. Abercrombie recommended that a military trail be built inland from Valdez by a route which would avoid the glacier. This was authorized in 1899, and during the summer, Abercrombie constructed a horse trail to the summit of Thompson Pass, thus surmounting the most serious obstacle to inland travel. During the following five years a crude pack trail was built through to Eagle on the Yukon, under appropriations granted by the War Department. Good service was rendered the pioneers by this trail, but its construction is chiefly significant in being a forerunner of splendid work done by the Army in road construction in Alaska.

Since the law of 1904 was found futile in opening up Alaska, a new statute was enacted in 1906. This provided for an Alaska Road Commission of three Army officers, one to be detailed from the Corps of Engineers. This board was authorized to construct and maintain military and post roads, bridges, and trails from funds collected by the existing license taxes outside of incorporated towns. Thirty percent of these taxes was reserved for maintenance of schools for whites, and 25 percent for care of the insane; the remainder was to be used for road construction and to this was added a direct appropriation of $150,000. This law marked the real beginning of road construction in Alaska, and its beneficial effects have been felt throughout the Territory ever since its enactment.

The original act left but little to to be desired. Its immediate and continued success, however, was almost entirely due to the fact that Brigadier General (then Major) Wilds P. Richardson, a man of exceptional executive ability, was chosen to be president of the board and continued in this office until 1917 when he recalled for military duty. At the time of his detail, General Richardson had had eight years of almost continuous service in the Territory, during which time he had pioneered on the Yukon, built trails, and established Army posts. These duties had given him a broad knowledge of Alaska and her people, and his duties in road location and construction soon made him the leading authority on the subject of Alaskan transportation. His duties and responsibilities were arduous; for not only had he to carry on road building under very adverse physical conditions, but also he had to meet constant criticisms from local residents who could not realize that an annual grant of only a few hundred thousand dollars could not begin to meet the needs for wagon roads.

Richardson was quick to grasp that the crux of the transportation problem was to establish a trunk line of communication between open waters on the Pacific and the inland region. He, therefore, almost at once established a sled road between Valdez on the coast and Fairbanks, the largest settlement in the interior, a distance of 370 miles. Year by year, this route was improved, and it passed by successive stages, from dog trail, to sled road, to wagon road, and finally to a fair automobile road. For years, this was a main artery of mail routes and passenger trail into the interior, and it has only recently been superseded by the completion of the government railroad. Richardson’s vision extended even further, for he conceived the bold project of an extension of this road through to Nome, thus giving an overland route to this remote community. This larger project he unfortunately could not carry out because of lack of funds. In addition to the main highway, now known appropriately as the Richardson Road, many local roads and trails were also built.

Richardson’s many years of service devoted to the interests of Alaska are one of the outstanding features of federal administration of Territorial affairs. After his return to military duty, his work was most efficiently continued by the officers of the Engineer Corps to whom the task was assigned. By 1920, the Commission had built 4,890 miles of road and trail, of which 1,031 miles were wagon road. There had been expended in construction and maintenance a total of $5,498,000, of which $3,370,000 were from direct appropriations and the rest from local taxes. Meanwhile, some roads and trail had been built by the Forest Service and by the Territorial Road Commission.21 Thus great progress has been made, but the industrial needs of the Territory demand at least an equal mileage of roads and trails to that already constructed.

One of the most important acts of Congress for the benefit of Alaska was the authorizing in 1900 of military cable connection with Alaskan ports, the establishment of land telegraph lines, and wireless stations. The original act was passed, largely through the personal efforts of Major General A. W. Greely, then chief signal officer. Thanks to Greely’s efforts, cable communication with Juneau and other Alaskan ports was established by 1903, and by that time land lines had been extended over much of the inland region.22 Later, all important Alaskan towns were given some from of electrical communication cable: telegraph, telephone, or wireless.

The first aids to navigation in Alaskan waters were fourteen buoys placed in Peril Strait in 1906.23 The hundreds of vessels which traversed Alaskan waters during the Klondike excitement, carrying thousands of passengers and millions of dollars worth of freight, were transported through these dangerous waters with hardly a single aid to navigation. The losses of ships in Alaskan waters have been appalling. These were in part, of course, due to the natural physical conditions; but they are chargeable also to the lack of sufficient aids to navigation and the lack of adequate charts, a problem which the Coast Survey, with its very limited facilities,24 has tried hard to meet. Alaska’s vast shore line still has only one life-saving station, which was established at Nome in 1905. The Revenue Cutter Service, now the Coast Guard, has, however, from the beginning of its cruises in northern waters rendered much aid to wrecked vessels and has been the means of saving many lives.

-

ed.: This essay was seemingly written some time between 1920 and Brook’s death in 1924. ↩︎

-

Cf. “Railroad Routes in Alaska.” Report of Alaska Railroad Commission, and Congress, 3rd session, H. R. Doc. 1346, 1913, pp. 114–130. ↩︎

-

The Russians had only small coastal vessels driven by steam, their trans-Pacific traffic being all by sailing vessels. ↩︎

-

C. L. Andrews, “Marine Disasters of the Alaska Route,” Washington Historical Quarterly, 7, no. 1 (1916): 24–37. ↩︎

-

In 1878, the entire expenditure for the Alaskan mail service was $18,000, which provided monthly service to Sitka and Wrangell. By 1898, only seven post offices had been established in the Territory. In 1920, there was a total of 159 post offices of all classes. ↩︎

-

A speed of nine miles an hour for four hours has been recorded in some of the dog races. ↩︎

-

See Alfred H. Brooks, Blazing Alaska’s Trails (University of Alaska Press, 1953). ↩︎ ↩︎

-

D. H. Jarvis, Report of the Cruise of the U.S. Revenue Cutter Bear and the Overland Relief Expedition. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1899. p. 47. ↩︎

-

Sheldon Jackson, Fourteenth Annual Report on the Introduction Domestic Reindeer into Alaska (Washington, D.C., 1906), pp. 104–105. ↩︎

-

Hudson Stuck, Ten Thousand Miles with a Dog Sled (New York, 1914), p. 402, 407. ↩︎

-

The first trip above Fort Yukon, made in 1875, ascended the Yukon as far as the site of Fort Reliance, about six miles below Dawson. ↩︎

-

The Arctic brought the first cargo of provisions to the then newly-discovered Klondike in the fall of 1896, but soon was caught in the ice and wrecked. ↩︎

-

Gross tonnage, 800 to 1,211. ↩︎

-

During the Klondike days, wood for steamers was sold at $15 and $25 a cord, but the normal price is $4 to $8. ↩︎

-

In addition, there were 620 miles of winter sled road and 250 miles of improved trail. ↩︎

-

Government railroad construction at this time was beginning to rectify matters. ↩︎

-

The law provided that the toll rates must be approved by the Secretary of the Interior. ↩︎

-

The price paid for the wagon road was $40,000. ↩︎

-

Alfred H. Brooks, “Placer Mining in Alaska,” United States Geological Survey Bulletin, no. 225, Washington, D.C., 1904, pp. 56–57. ↩︎

-

It is worthy of note that C. W. Purington, then of the Geological Survey, was the first to present definite estimates of the cost of road construction in Alaska and to substantiate by actual figures their need to the placer mining industry. See his “Roads and Road Building in Alaska,” Ibid., no. 263 (1905). pp. 217–228. ↩︎

-

It is estimated that the cost of wagon road construction in Alaska at the prices of 1920 will be from $5,000 to $6,000 a mile. ↩︎

-

It should be remembered that the Western Union Telegraph Company built and operated some fifteen miles of telegraph line in Seward Peninsula as early as 1867. The construction of long distance private telephone lines was begun at Nome in 1900, but telephones had by then been in use for a number of years at Juneau. Nearly all Alaskan towns of over 400 population have a telephone system. ↩︎

-

The Russians had one lighthouse in Alaska. This was a light placed in the cupola of the Baranof Castle at Sitka. It was maintained by the Army for a few years after the annexation and then abandoned because of lack of funds. ↩︎

-

In 1920, about ten percent of Alaskan waters had been charted in the detail needed for navigation. ↩︎